Bernhard Schmidt

Bernhard was born in Munich in 1956.

When his parents brought him a Minolta SLR camera from a trip to Asia at the age of 16, his passion for photography was completely inflamed. He spent a lot of time in the darkroom developing his films and pictures. A few years later it was clear that he wanted to become a photographer, so he developed a portfolio with which he could apply to the famous Folkwang School in Essen.

After studying there, he moved back to his hometown of Munich. Since then he has been working as a freelance photographer. He has worked a lot for fashion companies, advertising agencies and magazines. Photo trips and reports were and are another focus.

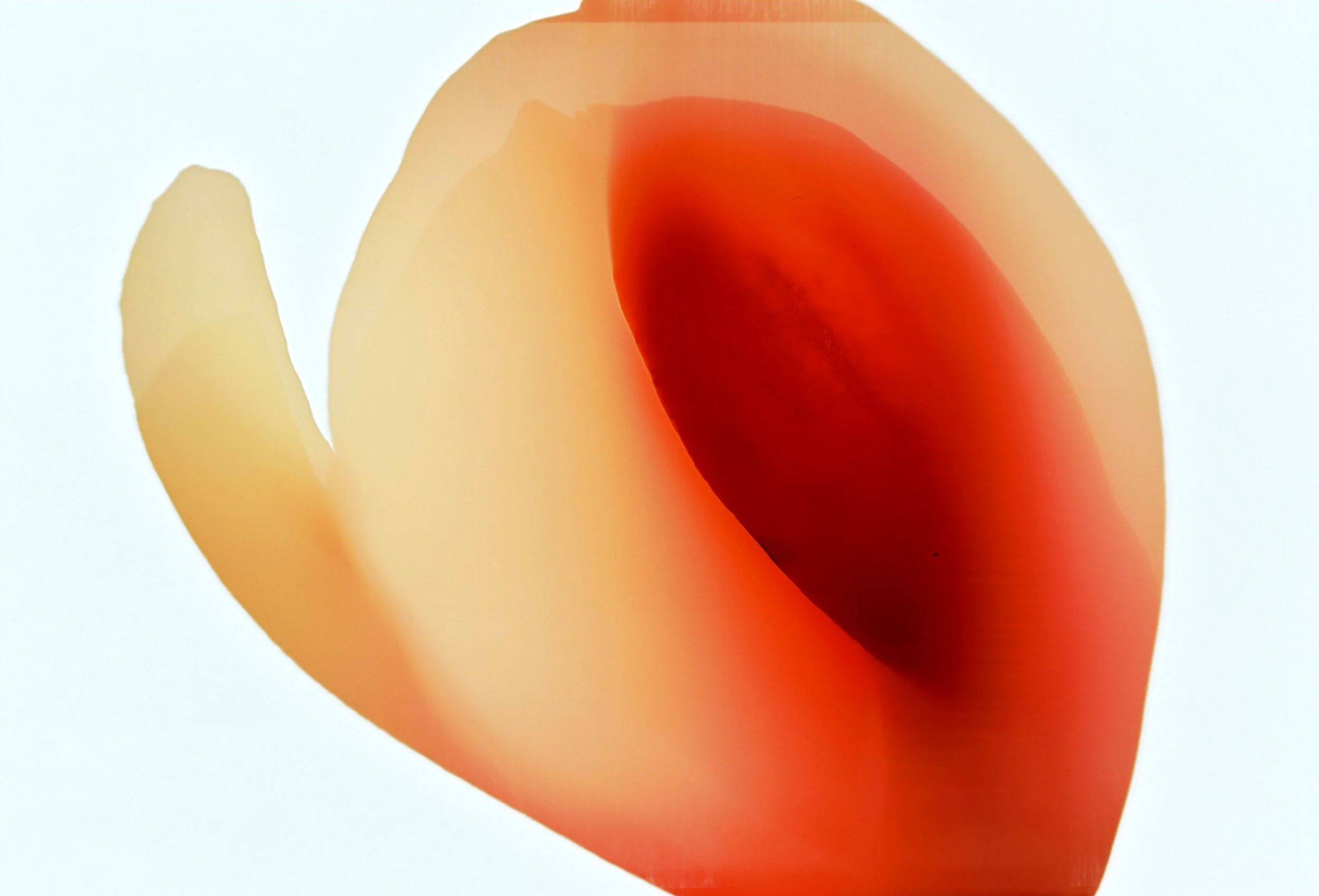

All the while he was experimenting with photograms. This technology continues to fascinate him to this day. Because of the uniqueness of the pictures, because people or objects touch the paper directly and because there is always a certain secret to it.

You can see the outlines, you can see an unbelievable sharpness in the places where there was direct contact with the photo paper. At the same time, there is enough leeway to imagine what the whole thing looked like, what happened before and after the exposure.

Communication Design/Photography Diploma Degree with professors Erich vom Endt and Inge Oswald at the Folkwang University Essen from 1979 - 1985.

1992 Solo exhibition with large scale erotic works at Galerie Holzheimer, Munich.

1999 "New Light" commissioned solo exhibition at Osram Headquarters, Munich.

2002 "Ambrosian Fields". Ederer, Munich.

2010 "Craving" commissioned solo exhibition at ZI, Mannheim.

2015 "Bright Lights". Solo exhibition at Hochschule für Fernsehen und Film (HFF) and Brillen Schneider, Munich.

2023 "Taste of Light" Solo exhibition Galerie in der Borstei, Munich.

2025 January-February "Miles Ahead" Solo exhibition Brillen Schneider, Munich.

2025 April "Bright Lights" went Hollywood at TheOtherArtFair in Los Angeles.

Bernhard, your photograms embody a rare tension between control and chance, precision in placement and lighting, yet surrender to the medium’s unpredictability. How do you reconcile authorship in a process that depends so heavily on accident and intuition?

I try to follow my intuition..

Of course, my experience with the technique plays an important role. It creates a certain tension and anticipation of the result - hopefully what I’m going for. And it also involves a good portion of chance, of things that were not foreseeable.

Photograms bypass the lens entirely, removing the traditional 'eye' of the photographer. In doing so, do you feel you're challenging the viewer’s expectations of what photography ought to be or perhaps even redefining what it can be in a post-digital age?

I can't and don't want to redefine the viewer's expectations of photography. That seems a little presumptuous to me, especially now in the digital age. But being able to put those expectations to the test is certainly one intention. It is in the nature of this art that, in principle, forms are visible at first. The beholder has to fill the content of those forms with his own imagination. That is not the norm and a certain challenge.

Your work speaks eloquently in silence, outlines, contours, and spectral imprints. How do you approach narrative in a medium so deeply abstract, and how much of that narrative is intended versus discovered after the fact?

I can answer this question in a similar way to the first:

Intuition is the baseline, the the basis of my narrative, so to speak.

However, individual chapters are then also repeatedly written about what becomes visible in the final result.

From musical instruments to seasonal memories, your subjects are said to be "anything motionless" yet your images vibrate with emotional frequency. How do you translate intangible feelings like nostalgia or harmony into this camera-less process?

The emotions are transposed into the objects that on the photographic paper. It is difficult to describe exactly how this happens. What is certain is that there is a kind of magic in it. That’s the secret of the whole process.

As someone whose practice is deeply analog, labor-intensive, and singular, how do you view the contemporary obsession with instant imagery, digital manipulation, and viral reproducibility?

In principle, technical development cannot be stopped, especially in photography. It has developed at an exponential rate and it is obvious that a wide range of new possibilities, which can certainly broaden the horizon, need to be utilized.

However, as with all technical developments, the laws of nature and physics apply here too and cannot be overridden. They set a clear limit to the whole thing. The wheel cannot be reinvented.

The addiction to “higher, faster, further”, the new norm, is nevertheless going in new directions. The combination with artificial intelligence, however, takes the whole thing to a level that, in my opinion, no longer has anything to do with photography. I am very suspicious of this.

The photogram technique has a long, avant-garde history from Moholy-Nagy to Man Ray. Do you feel bound by this lineage, or do you see your work as part of a reinvention, a contemporary reactivation of a forgotten form?

Neither. On the one hand, I am of course part of this tradition. I didn't invent photography or the photogram technique, nor am I the only one who uses them today. And of course avant-garde role models such as Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy as well as a contemporaries like Florian Neusüss have influenced me. And tradition simply always means passing on the flame.

On the other hand, I want to take a modern approach, develop the technique even further, make it accessible to contemporary sensibilities and broaden horizons.

You mention that the “moment of truth” comes only after development and that failure is not uncommon. In an era that prizes efficiency and perfection, how do you personally embrace failure as a vital part of your artistic discipline?

Failure is part of it. Mistakes happen. There are many ways to make them. You have to accept that. When you do, you can learn from them.

As I mentioned at the beginning, chance can play an important role.

If it generates something positive, wonderful!

If there are negative surprises, that is of course not so nice. Being open to this make disappointments less bitter.

In a cultural climate that increasingly demands that art be political, topical, or socially engaged, how do you defend the importance of creating work that is meditative, poetic, and by your own definition, soul-nourishing?

I generally refuse to accept demands that are made by changing cultural climates, by social or political constraints. I do not put on the corset of the politically correct activist zeitgeist.

I like freedom - not just as an artist. I want to do what I feel like doing. just want to do what I want. If there is a compulsion to express political opinions in art so that they are taken seriously and count, then that is nothing but dictatorship for me.

There is a spiritual quality to your process, the darkness, the blind composition, the act of faith in light and chemistry. Do you see your photograms as ritual objects, evidence of a private encounter between the seen and the unseen?

A resounding yes!. My work is extremely personal. Working in complete darkness is always a ritual encounter of an unforeseen kind.

If the role of the artist is to provoke, heal, and unite as you suggest, how do you see photograms contributing to that mission in a fractured, hyper-visual world? Can stillness be a form of resistance?

That's a very good and important question. As I said earlier, I generally refuse to accept externally imposed expectations and just want to do my thing.

If my work is perceived by the viewer as being “unlocked” from such demands and is still liked, then this task is largely fulfilled.

And yes: silence can be a form of resistance!