Daniel OLIVIER

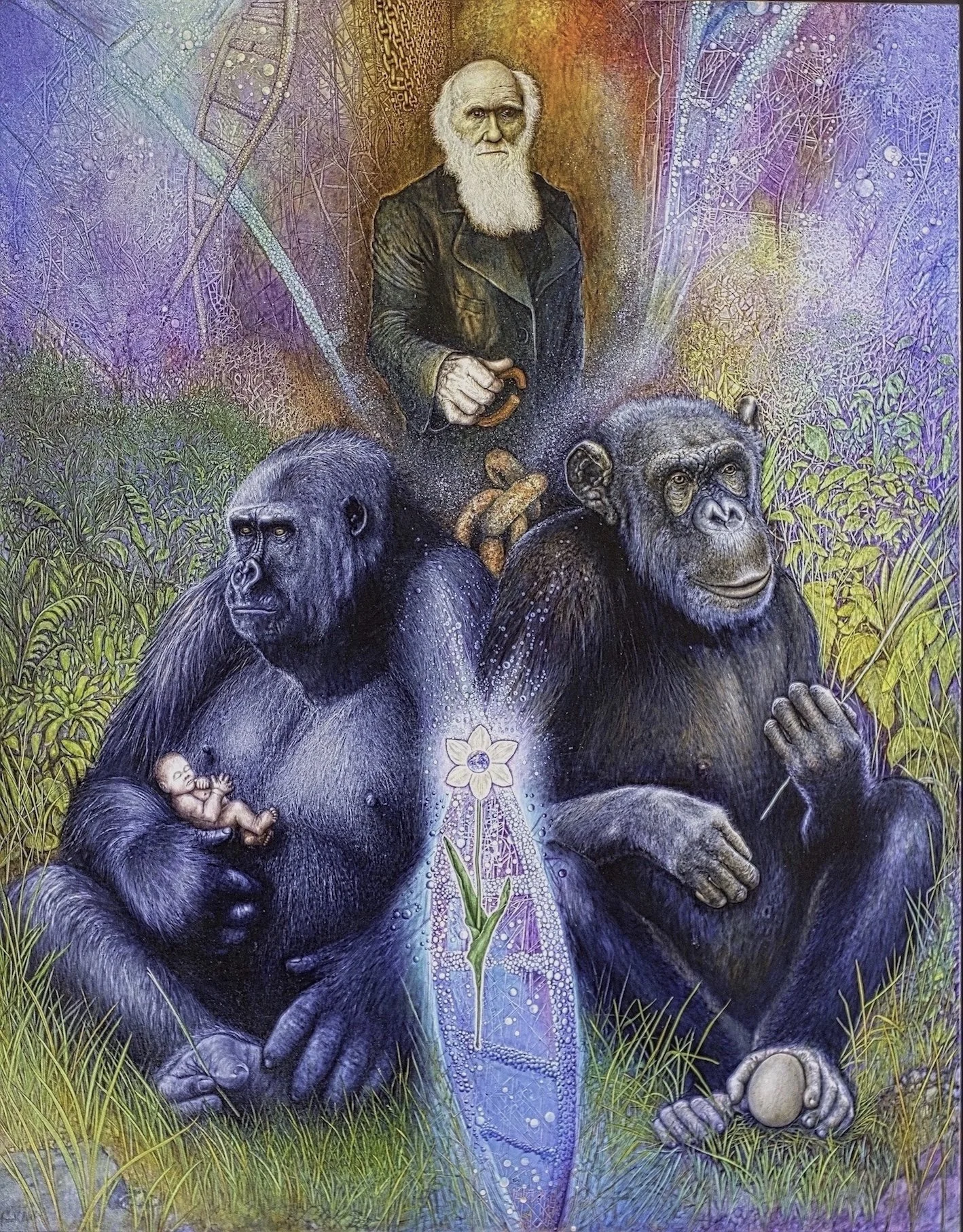

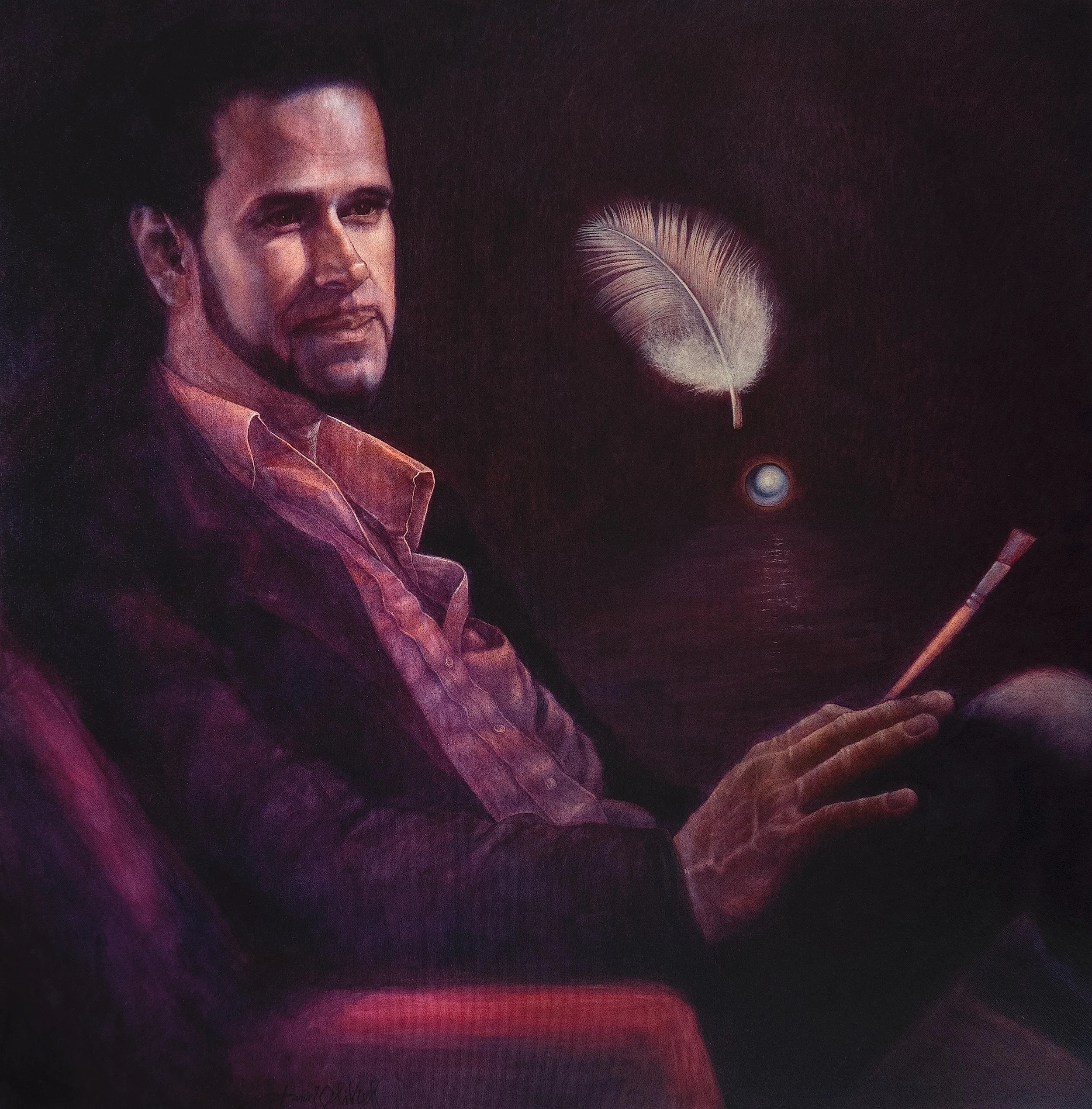

Daniel Olivier, born in 1950, is a figurative painter working in oil, exploring transparency and glazing within a symbolic and poetic imaginary. He is a member of ADAGP, the Taylor Foundation, Mondial Art Academia, the Maxi-Réalistes group of Dan Jacobson at Comparaisons, and the Circle of European Artists. He is a full member of the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Artistes Français. He lives and paints in Auvers-sur-Oise, France. His first solo exhibition took place in May 1970. Bronze medal of the Artistes Français, 2024. After years of exploring abstraction and freer figuration, since 2020 he has returned to a practice grounded in his imagination, painting with a technical approach inspired by the great masters: Leonardo da Vinci, Salvador Dalí, Jean Olivier Hucleux, Rembrandt, Van Eyck, and Velázquez.

Daniel, your paintings unfold on a scale that seems to mirror both the intimacy of the cell and the immensity of the cosmos. They invite the viewer to inhabit a vertiginous space where the infinitely small enters into dialogue with the infinitely vast. How do you experience this oscillation of perception in your practice, and do you believe painting itself can serve as a channel through which the gaze crosses otherwise invisible thresholds?

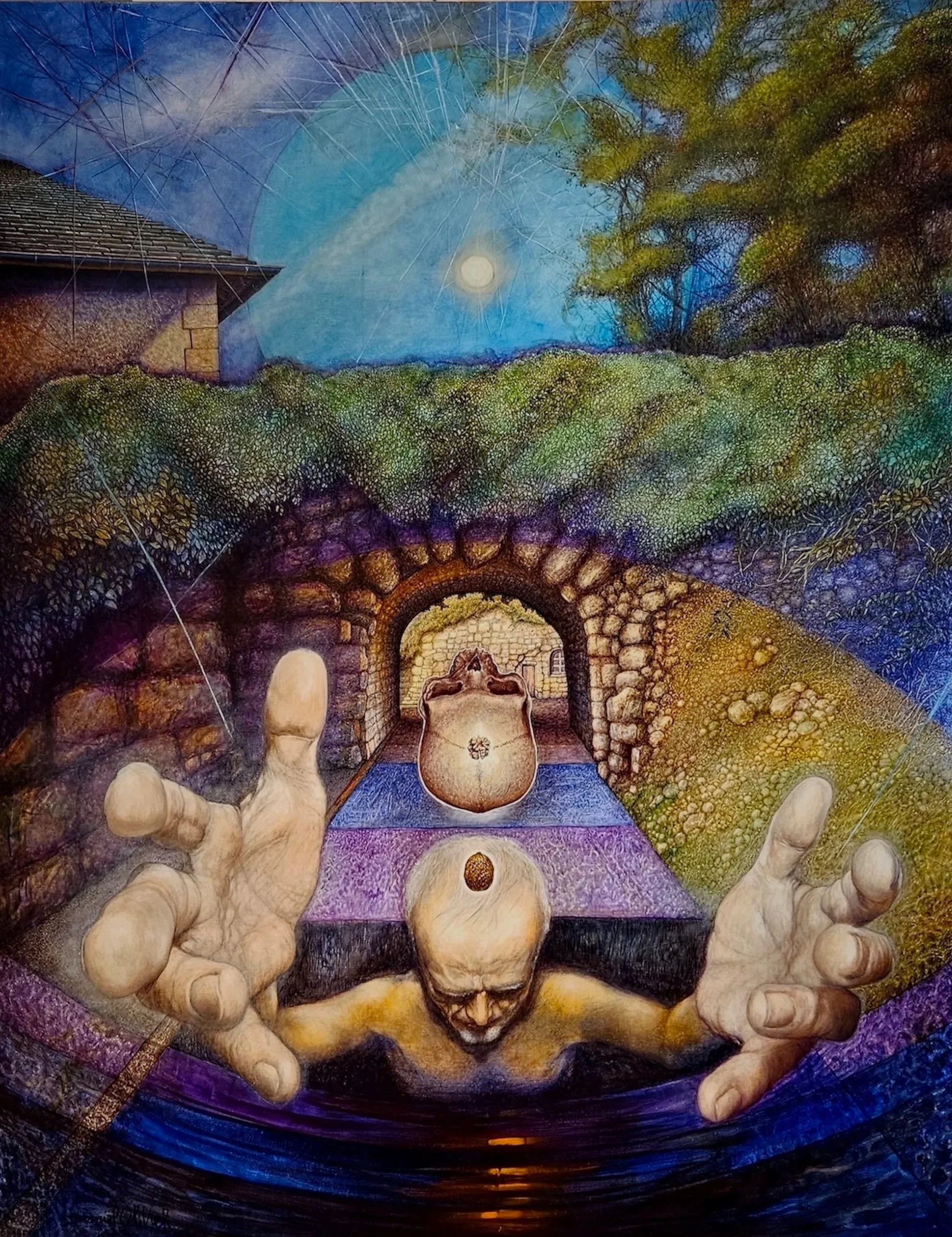

Without invoking the divine, yet without denying it, I feel deeply that within our very cells we are in unison with the universe, imbued with it, vibrating in harmony. Through the channel of painting, it becomes possible to cross into the invisible, even the unspeakable, by surrendering to the image as it takes form. There are always two stages for me: first, the conception of the work, and then its realization. In the act of painting, I surrender to the medium in what I consider a form of active meditation. I do not control—it is the painting that guides me, navigating between the rigor of the project and the free listening of the improvised gesture. I feel connected, humble, simply a hand with a brush, an instrument through which painting itself acts.

Transparency, superposition, the slow accumulation of shadow and light: your canvases reveal the rigor of a classical discipline while radiating an imagination that veers toward dream. To what extent do you continue the dialogue with the great masters of the past, and at what moment does their legacy dissolve into a language uniquely your own?

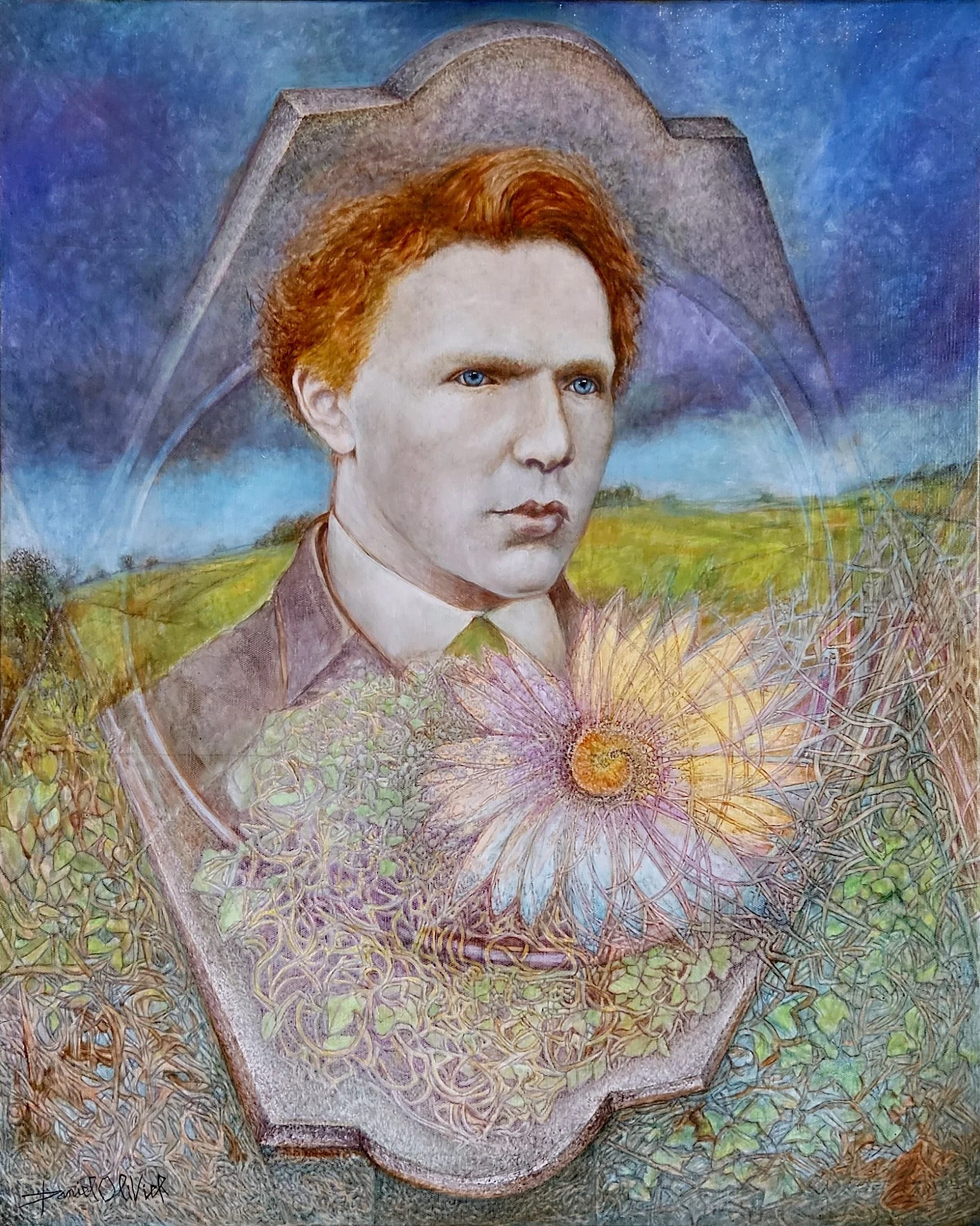

I believe that the great masters of painting, from beyond, still speak to painters. They watch over us with compassion, support us, assist us. Living in Auvers-sur-Oise, I often visit Vincent Van Gogh’s grave, where in silence I say to him: “How are you today, I’m thinking of you, I need your help.” Respect for heritage—whether in the image itself, in relation to history, or in the technical process—is essential to me. But once that stage is passed, one must take flight, leave the branch, and paint with one’s own voice. When the great masters extend the baton, we must open the doors of our own imagination and cultivate our technical language. When I paint, I feel them behind me, urging: “Go on… move forward, we are here.”

At the core of your method lies a paradox. On one side, the solitude of the studio, the silence where painter and canvas breathe together. On the other, your practice of painting in public spaces, along riversides and in gardens, which invites the unpredictable presence of strangers. How does this duality shape the inner life of your work and alter the resonance of the images that emerge?

After five years of relentless work in the silence of the studio, painting in public came as a kind of equilibrium. The chance encounters with strangers, or the recognition of friends, bring joy, exchange, and diffusion of the work. It is like a musician in concert, receiving applause—an infusion of positive energy that nourishes the spirit and compels me to create freely, in joy, with images full of light and beauty.

Nature in your paintings is not a passive landscape. It vibrates, remembers, and radiates with symbolic force, as though it were a sacred text. Do you see your work as part of a wider movement to re-enchant the natural world, and how do you navigate the tension between poetic symbolism and fidelity to observation?

Your words resonate with me: the symbolic force of nature, its kinship with sacred text. Indeed, I believe that nature, and all things, are governed by such a sacred text of symbols. To re-enchant the natural world is to learn, in silence, how to look at it. A tree is not simply a tree—it is the hand of the earth stretched toward the sky. A branch is not just a branch—it is a trajectory of growth inscribed in space, with its own architecture, its own energy. Foliage moves in currents like ocean tides or clouds in flux. I imagine these currents as fractals, repeated infinitely, the primal symbol of the sacred text. Painting becomes a poetic act, both symbolic in its construction and imaginative in its resonance, but above all, it echoes the most beautiful of all symbols: beauty itself.

You once described the brush as a link to the profound mystery of life. It is a tactile definition of painting that suggests the act itself is inseparable from a metaphysical search. After more than five decades of practice, what has this sustained tactile encounter revealed to you about life, time, and the fragile boundary between the visible and the invisible?

Metaphysical is the right word. Salvador Dalí said of Jean Olivier Hucleux: “He is not hyper-realist, he is hyper-metaphysical.” I cite these two geniuses in my biography—Dalí as my mentor, Hucleux as a great French master, out of duty of memory. In France I am often presented as a hyperrealist painter, though this is not what I seek. I strive to make painting of fine quality in service of the imagination. Painting is indeed a tactile act, born of listening and surrender, a profound dialogue with what lies beyond the self. In painting, I find myself flirting with the threshold between visible and invisible. I believe I was made to paint—without reason, without explanation, without even a question.

The circular, the orbital, the cyclical—these geometries recur in your work like constellations guiding the imagination. They echo celestial movements, but also organic patterns of growth and decline. Do they appear intuitively, as signs breathed onto the canvas, or are they the result of a conscious meditation on time, matter, and the infinite rotation of existence?

The circular gesture is the body’s energy projected into space. It is a kind of buttress of life, an extension of the self. The circle fuses body and space, the inner biological world with the universe in its ceaseless circular motion. I never asked myself why I return to it—it comes intuitively, even sensually. But the sphere, present in most of my works—sometimes discreetly in the composition, sometimes explicitly as subject—is a deliberate symbol. For me, it signifies the center of being, the presence of love, the divine.

Your choice of materials is never neutral. Oil, amber, wood, even the humble ballpoint pen—each carries its own aura, charged with history, memory, vibration. How do you allow each material to speak, and in what way do you feel matter itself holds the hidden narratives that your paintings reveal?

Since 1967, when I made my first oil painting, I have explored many mediums—pastel, pencil, watercolor, graphite, ballpoint pen, oil. Each reveals its potential through use. In public, I now work with ballpoint pen, discovering its subtleties: from sharp lines to delicate blurring almost impossible to achieve. The pen itself guides me, leading me into improvisations, and I play with it joyfully. Graphite and lead offer endless nuance and possibility in drawing. Oil painting, however, opens the door to infinity. Incorporating amber—after long study of the Flemish painters and of Leonardo da Vinci—I discovered the alchemy of glazes, an endless dialogue of layers that guides my hand and transforms my gesture.

To live and paint in Auvers-sur-Oise is to inhabit a landscape haunted by artistic ghosts, steeped in memory and vision. Van Gogh’s presence lingers, as do the echoes of generations of painters who sought the ineffable beneath these skies and among these trees. How does this charged place shape your imagination, and do you feel that your work enters into a silent dialogue with this lineage?

Van Gogh once said: “Auvers is gravely beautiful.” It is undeniable: this place is saturated with history. The soul of painting hovers here—in the silence, the beauty, the tranquility. I feel carried and guided. Here, creativity comes naturally, accompanied by the ghosts of painters. The old walls, the lanes, the church, the water’s edge—all open onto the simplest and most profound of emotions: peace, and with it, serenity. Surrendering to this landscape is to join a great family history, one that lives on in this village of artists.

You often return to three elemental forces: the gaze, the hand, and the light. One could say they form the invisible architecture of painting itself. Yet they also resonate as metaphors for human existence—for how we see, touch, illuminate, and are illuminated. How do you interpret the dynamic between these three forces, and what space do they open in your art?

Fraternally or lovingly, the gaze of another, carrying light in the eyes, can touch your heart, your soul, often more profoundly than the hand, illuminating your life. In one sentence, this summarizes the bond between these three forces—the profound dynamic of life, the chain of union. The gaze of the other opens the doors of inner vision, teaching you how to become yourself. In my painting, which comes from the deepest part of me, it is the hand that realizes, that shapes, that searches for meaning and for light. My painting is perhaps a hand extended, seeking the gaze of the other.

Over the decades, your path has woven figuration, symbolism, transparency, and poetic abstraction, always carried by a thread of curiosity and a will for encounter. Considered as a whole, your oeuvre resembles a vast journal of perception, sensation, and vision. With distance, what do you see as the inner continuity that binds it all together, and what do you hope a future gaze will discover in this dialogue between your hand, the canvas, and the inexhaustible mysteries of life?

It has always been a search for beauty, for meaning, for light—carried by a constant concern for sincerity and authenticity, always aligned with the present moment, made of doubt and of wonder. This has been the guiding thread of my work for decades. Having found peace, the joy of creating, I hope that each person might find in my paintings a part of themselves. My work is an inner encounter; may those who look at it find personal enrichment, an opening, a poetic and friendly sharing of life.