Graciela Cassel

Graciela, your work often bridges scientific inquiry with poetic abstraction. How do you navigate the balance between empirical observation, such as the physics of tides or the optics of light, and the deeply personal, emotional responses that inform your practice? Where do you see the boundary, if any, between science and art dissolving in your work?

For me, science and art are not opposites but parallel languages. Science observes and measures phenomena, while art translates those same forces into emotion and memory. I use observation to structure rhythm and form, and then let my own emotional responses expand the work into abstraction. The boundary between science and art dissolves when both reveal what is otherwise invisible—energy, connection, and the fleeting nature of time.

You speak of being “immersed” in nature as essential to your creative process. Can you describe a recent moment in nature that profoundly shifted your perspective as an artist? How do these immersive experiences translate, sometimes unexpectedly, into the textures, colors, and forms we see in your work?

Recently, while standing by the Hudson River, I watched the tide shift and carry reflections of the city skyline. In that moment, I saw both my childhood delta waters and New York’s river converging. That sense of continuity and transformation found its way into the studio as layered washes of watercolor—transparent, overlapping, resisting fixity. These experiences often reappear in my work unconsciously, shaping textures and rhythms.

Your “Oceans” series abstracts the cyclical rhythms of the sea, embedding both personal memory and scientific phenomena. How do you see abstraction as a means of deepening rather than distancing our understanding of natural forces? What can abstraction offer us that realism cannot, particularly in the context of environmental reflection?

Abstraction allows me to get closer to the essence rather than the surface. The sea is not only waves—it is rhythm, renewal, loss, and memory. Realism can capture appearance, but abstraction can convey resonance, inviting viewers to feel the ocean within themselves. In terms of environmental reflection, abstraction offers empathy, a space to sense our interconnectedness rather than simply observing from outside.

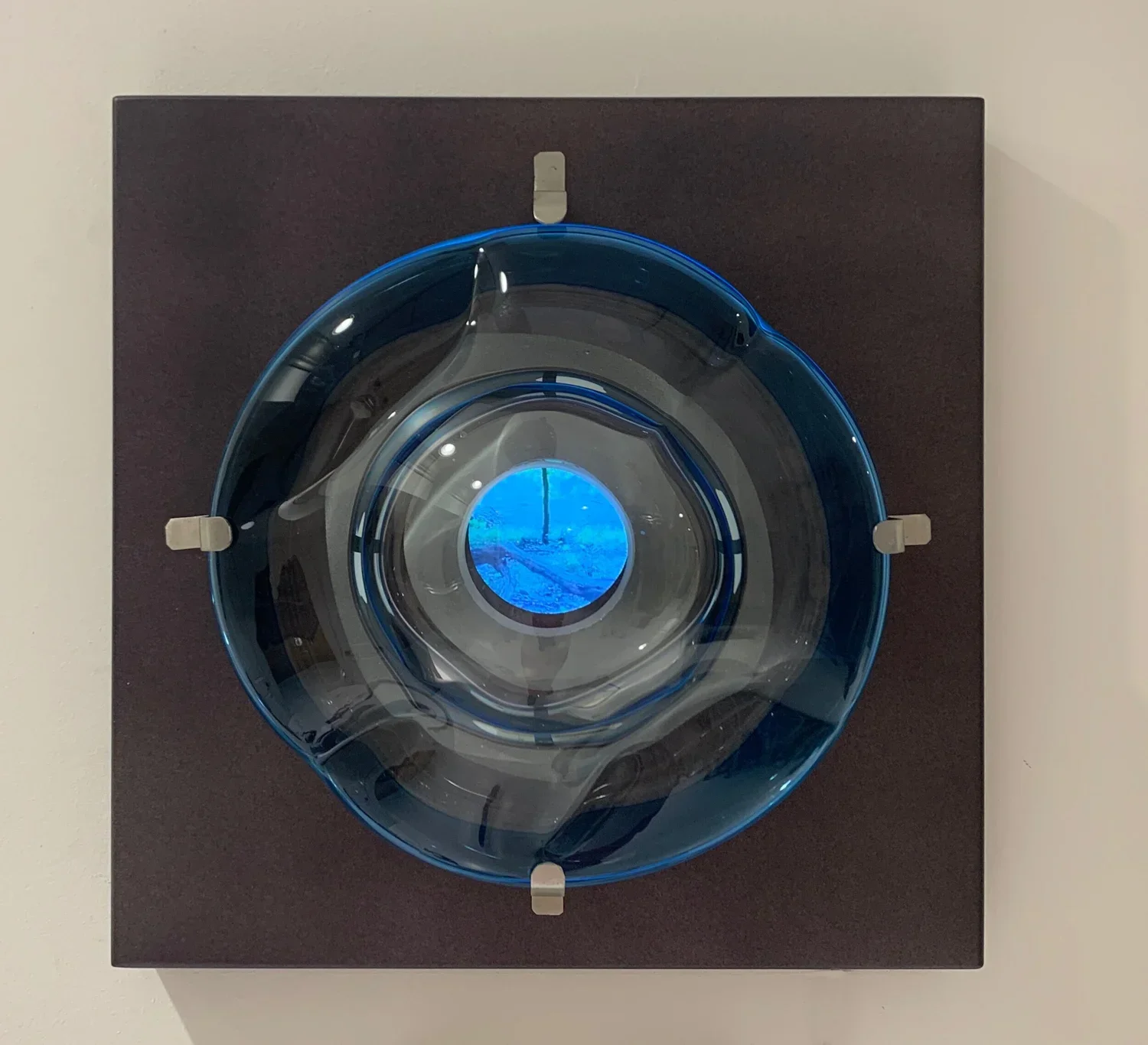

Your works are deeply tactile with layers of watercolor, glass beads, and metallic leaf. How does the physicality of your materials contribute to the intangible qualities you aim to evoke, like fluidity, light, and the ephemeral? How do you choose your materials in relation to the conceptual essence of each piece?

Each material carries its own voice. Glass beads suggest drops of water, metallic leaf recalls fleeting glints of sunlight, watercolor flows beyond control like a tide. Their tactility makes the intangible—fluidity, light, impermanence—almost palpable. I let materials guide me, aligning their physical properties with the conceptual essence of each piece.

Having grown up in Buenos Aires’ delta region, a confluence of rivers, land, and sky, you’ve mentioned how this environment shaped your perception of change and transformation. How does this early experience with a mutable landscape continue to resonate in your New York-based practice today, especially when confronting the more rigid structures of urban life?

The delta taught me that land and water are always negotiating space, eroding and rebuilding. That sense of flux remains with me in New York, where the city often feels rigid and unyielding. My practice becomes a way of reintroducing fluidity into urban structures, reminding myself—and others—that nothing is fixed.

Transborder Art, the platform you founded, creates conversations that cross geographical and disciplinary borders. How has facilitating these dialogues informed or transformed your artistic inquiry? In a world increasingly fragmented by borders, what role do you believe art plays in fostering transnational or transdisciplinary understanding?

Transborder Art grew out of a desire to create conversations beyond geography and discipline. Listening to other artists taught me that art is not only personal but also a collective archive of perspectives. In today’s fragmented world, art remains one of the few languages that can cross borders without translation. It fosters empathy, shared responsibility, and connection across difference.

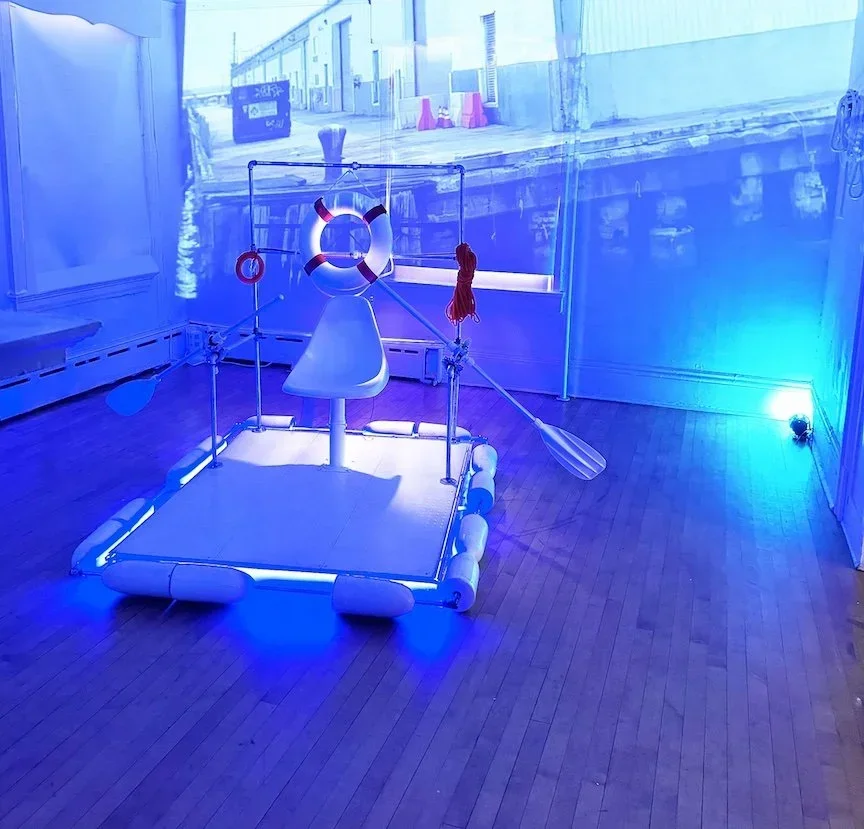

Your installation work frequently invites immersive sensory experiences that blur the line between artwork and environment. How do you envision the role of the viewer in your installations? Are they passive observers, active participants, or even collaborators in the unfolding meaning of the work?

Viewers are essential participants. My installations are not complete until someone enters them, bringing their own body, memories, and senses. I design spaces for wandering, reflection, and even disorientation. In that sense, the viewer becomes a collaborator in meaning-making—the work unfolds through their experience.

In both your "Oceans" and "Gardens" series, nature is not only your muse but a metaphor for larger existential and ecological questions. How do you see your work contributing to contemporary discourse on our environmental crisis? Do you consciously position your practice within ecological art, or do you see your engagement with nature as a more intuitive, personal journey?

My engagement with nature is intuitive and personal, but today that inevitably resonates with ecological urgency. I don’t frame myself strictly as an ecological artist, but my work carries a quiet call to protect what is vital and vanishing. By abstracting cycles of water, gardens, or skies, I hope to create emotional spaces for reflection, which are essential for ecological awareness and care.

Your practice emphasizes the translation of the unconscious and sensory impressions into visual form. How do you access this unconscious in your studio process? Are there methods, meditative, spontaneous, or research-based, that help you bypass conscious control and allow intuition to guide your work?

My process balances research and surrender. I might begin with maps, scientific studies, or sketches, but I eventually let go of control. Watercolor, for example, flows unpredictably, echoing the unconscious. I welcome those accidents. Silence, slow breathing, and sometimes music also help me step outside analytical thinking and allow intuition to guide the work.

Your pieces often reflect a fascination with invisible forces such as gravity, tides, and wind currents. If you could render any invisible phenomenon visible through art, what would it be and why? How might making the unseen seen alter our collective perception of the world around us?

If I could render any invisible phenomenon visible, it would be time itself—not as a clock but as a living current. Time is always shaping us, just as tides shape the shore, yet we rarely perceive its flow. To make time visible would remind us of impermanence and interconnectedness, shifting our perspective from possession to coexistence. Art, at its best, makes the unseen felt.