Natalie Egger

Website: https://www.unisonart.space/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/unison1089/

Natalie Egger, multi-award-winning Austrian artist and graduate of the University of Applied Arts Vienna, lives and works in Vienna. Her practice flows between photography, digital art, acrylic painting, and drawing - each medium a language of transformation. In her digital works, fleeting urban or travel impressions are layered, deconstructed, and reimagined, merging photographs (sometimes) with her own pencil drawings into new visual constellations. Her paintings and drawings focus on the human body and face, inspired by the gestures of dance, the intensity of theatre, and the elegance of fashion. Natalie’s works have been exhibited in museums, galleries, and art fairs in Austria, Italy, Spain, the UK, USA, China, Korea, Greece, Switzerland, and Kazakhstan. In July 2024 she celebrated her first solo exhibition in London. Her art appears in international publications, and several works belong to private collections in Europe and Asia.

My approach to art is a pursuit of creation for its own sake, echoing the principles of l'art pour 'art. The essence lies in the process of artistic creation, with less emphasis on the final outcome. At first glance, viewers may struggle to identify the subjects in my work. I intentionally focus on subjective perspectives, revealing only a fragment of the whole. Consequently, the subjects may appear differently than they would in reality, viewed from a conventional perspective.

Natalie, your artistic trajectory spanning photography, digital art, visual art, and street art seems to resist categorical fixity, instead unfolding as a living constellation where mediums converse with one another. How do you conceive of this interdisciplinarity: as a strategy, a necessity, or perhaps a natural byproduct of your restless curiosity?

For me, interdisciplinarity is less a strategy and more a natural unfolding of how I experience the world. Since 2015, I have been working across different fields - drawing, painting, photography, and digital art - and I have always felt that these mediums are not isolated territories but rather interconnected languages. Photography, for instance, sharpens my eye for composition, while drawing and painting allow me to translate what I see into something more tactile and intimate. Digital tools then offer the possibility to merge these registers, to create hybrid works where the boundary between the analogue and the digital dissolves.

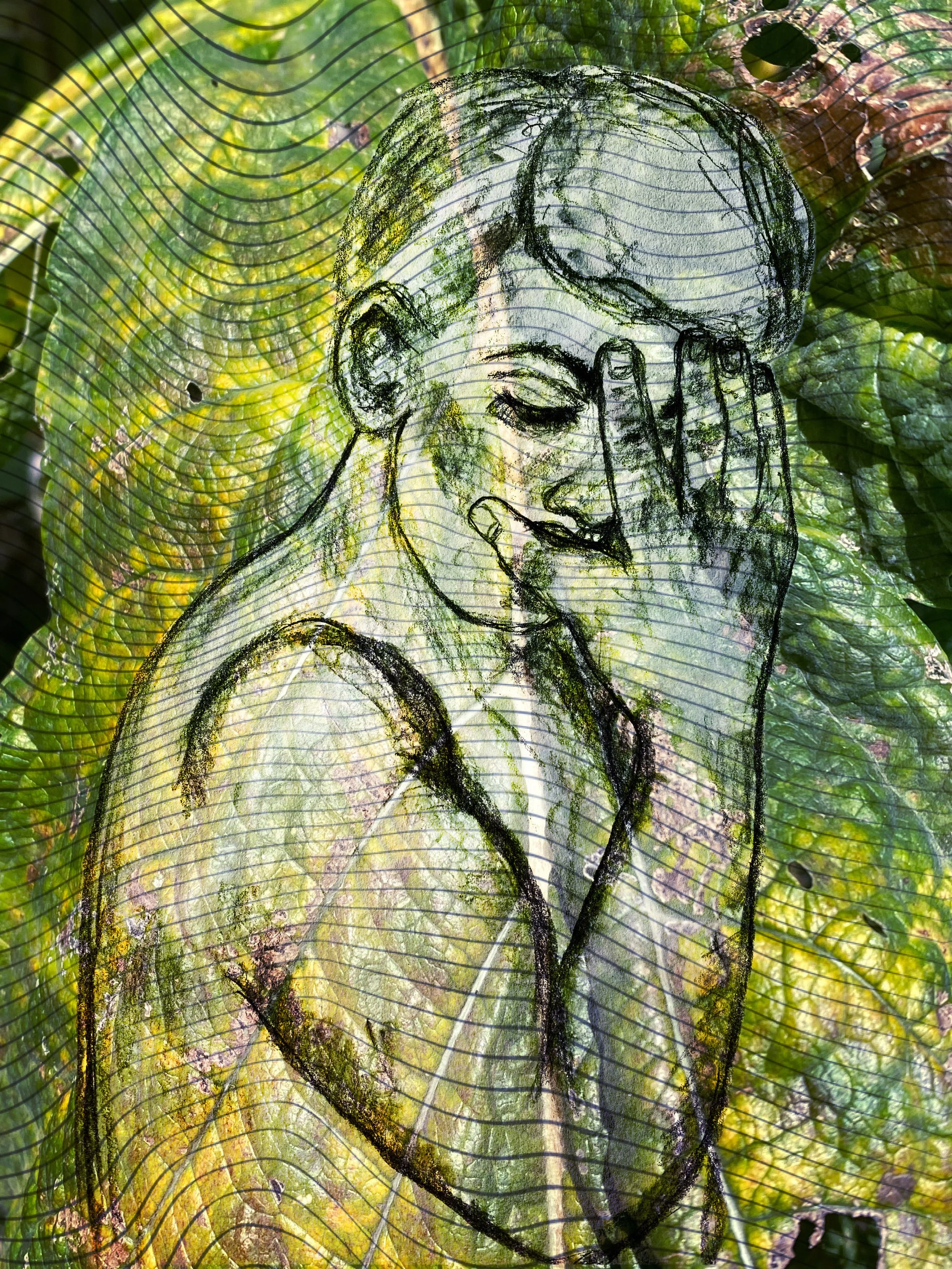

This movement between mediums is fuelled by my curiosity and by the environments I engage with: the encounters of city life and travel, the gestures of dance and theatre, the fragments of fashion, or the quiet structures of nature, like the veins of a leaf or the inside of a fruit. Each medium offers me a different access point, and rather than choosing one, I let them overlap and speak to each other. In that sense, interdisciplinarity is both a necessity - to do justice to the richness of what inspires me - and also a kind of organic rhythm, an instinct that keeps my work alive and in dialogue with multiple traditions, from the grand masters to contemporary street art and digital platforms.

In your triptych series juxtaposing the human form with natural motifs, you stage a subtle yet powerful dialogue between modern capitalism’s estrangement and the timeless rhythms of nature. Could you elaborate on how you understand the regenerative capacity of art, not only as a mirror of ecological crisis but also as an agent of re-enchantment capable of realigning humanity with its lost sense of belonging?

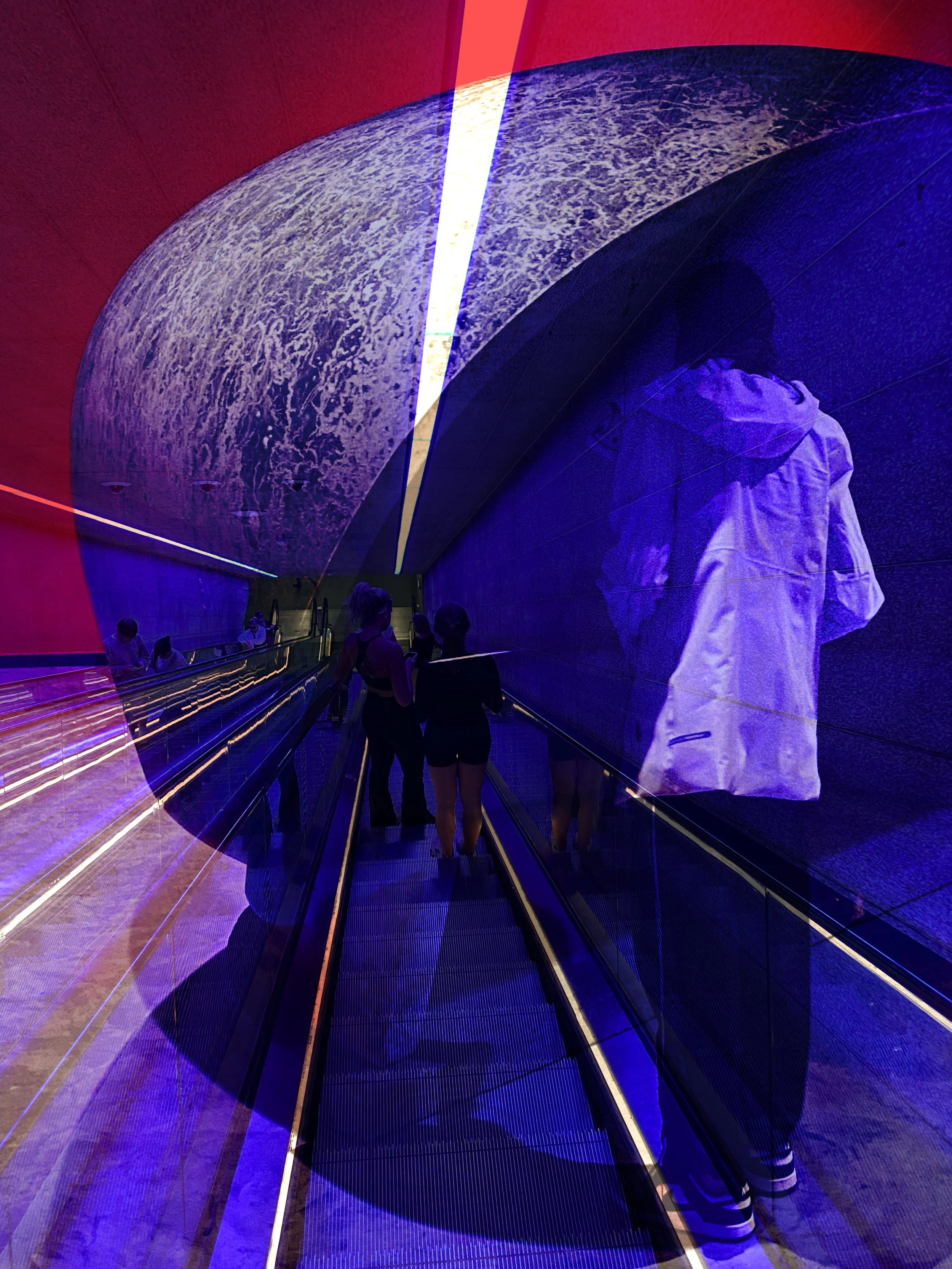

In that triptych, I wanted to create a moment of pause - a space where the human figure is no longer separated from its environment but becomes a vessel for it. The figure, with its back turned and hidden in a simple hoodie, is almost anonymous, a stand-in for all of us. By merging it with the organic textures of an algal bloom, the inner architecture of a shell, and the delicate surface of a clover flower, I was exploring how fragile yet resilient our bond with nature remains, even under the pressures of modern life and capitalism’s estrangements.

For me, art holds a regenerative capacity precisely because it can reawaken perception. We read headlines about ecological crisis, but often we have become numb to them. An artwork can cut through that numbness, not by illustrating catastrophe, but by re-enchanting the very details we overlook - the veins of a leaf, the shimmer inside a shell, the rhythm of water. This kind of attention is a form of care.

I don’t see art merely as a mirror reflecting loss, but as an agent that can realign us with our sense of belonging in the world. If someone looking at the triptych feels, even for a second, the quiet intimacy between their own body and the living textures around them, then that is already a small act of repair. It reminds us that despite alienation, the rhythms of nature are still available to us - and we can choose to listen.

Your master thesis on the influence of social networks on street art carved out an early, prescient position within contemporary discourse, particularly regarding the visibility of female street artists. Looking back from today’s vantage point, how do you perceive the shifting dynamics between digital circulation and street-level presence, and in what ways do you see yourself navigating these entangled spheres?

When I wrote my thesis in 2019, my focus was on Instagram as a disruptive and more democratic platform for street artists, especially for women. At that time, the art world was still heavily shaped by the so-called gatekeepers - curators, galleries, museums - that often carried an elitist attitude and presented real barriers for young female artists seeking visibility. Social media offered an alternative: it allowed artists to publish their work directly, to build communities, and to gain recognition outside traditional structures. I saw this as an opening, a way to rebalance a system that was far from inclusive.

Looking back from today’s vantage point, I see both continuity and transformation. Digital circulation has become even more powerful, but also more saturated, commercialized, and algorithm-driven. The promise of democratization is still there, but it comes with new challenges: visibility is no longer only about quality or innovation but also about navigating platform logics, attention economies, and sometimes the pressure to perform rather than create.

For myself, I navigate these entangled spheres by moving fluidly between them. The street still has its own presence, a raw immediacy that no digital screen can replicate. But the digital realm extends that presence, allowing artworks to travel, to be recontextualized, and to reach audiences across borders. I embrace this tension: the physical encounter with an artwork and the immaterial circulation online are not opposites for me, but complementary layers. Both are needed if we want to keep art accessible, critical, and alive.

There is a pronounced tension in your practice between the spontaneous, impression-driven gestures you describe as “turning off my head” and the structured rigor of academic research, drawing classes, and traditional figurative studies. How do you negotiate this duality between instinct and discipline, and do you see one as ultimately grounding or liberating the other?

Art, for me, is the place where thought loosens its grip. In my daily work I inhabit a world of words, facts, and figures - discussions and presentations that are precise but ultimately intangible. There, nothing is created that I can hold in my hands. In the studio it is different: I turn my head off. I just draw, I just paint. I let myself be kissed by the beauty of a motif that crosses my path - a human face, the folds of fabric, the structure of sand near the sea - and in that moment intuition carries me further than any calculation could. The act becomes a flow, a quiet surrender where the artwork seems to emerge of its own accord.

And yet, this freedom rests upon a foundation of discipline. The rigor of drawing classes, of classical figurative study, of academic research - these are like the grammar that allows a language to sing. Because the discipline is inscribed in my body, I no longer have to think about which pencil sharpens a shadow or which line balances a form. Instinct can take over, unfettered. In that sense, structure does not constrain but rather liberates me: it anchors the gesture so that intuition can soar. The tension between the two is not a contradiction, but the very pulse of my practice.

Dance, performance, and fashion enter your work as quiet yet decisive interlocutors, inflecting portraiture with rhythm, elegance, and corporeal expressivity. In what sense do you perceive the body not merely as subject but as medium, an embodied language through which motion, vulnerability, and grace are simultaneously inscribed?

The body has always been more than a subject for me - it is a living medium, a language in itself. In my drawings, especially the pencil series devoted to the human face and figure, I don’t see the body as an object to be represented but as a vessel of rhythm and expression. Dance and performance inspire me deeply because they reveal how motion inscribes itself into form: a turn of the wrist, the curve of a spine, the fleeting gesture that says more than words ever could. Fashion, too, interests me as an extension of the body - fabric that moves, conceals, reveals, and becomes part of the choreography of daily life.

When I draw or photograph the body, I try to capture not only its physicality but also its vulnerability and grace, the way it carries memory and emotion. A portrait can be a still image, yet within it lies movement: the aftertaste of a gesture, the echo of a performance. To me, the body is not static matter but an ongoing conversation between presence and absence, strength and fragility. It is through this embodied language that I explore how art can touch both the intimate and the universal - how the curve of a single line can resonate with the shared rhythm of being alive.

Your practice often merges pencil drawings with photographic elements, as though collapsing two temporalities, the immediacy of the captured moment and the slow, meditative unfolding of the hand. Do you regard these hybrid works as sites of reconciliation between technology and tradition, or are they meant to provoke viewers into questioning the ontological boundaries of image-making itself?

When I merge pencil drawings with photographic elements, I don’t begin with a fixed concept of reconciliation or provocation. For me, it is first of all an intuitive, creative act. I allow the two mediums to guide me through the process, and I never fully know the outcome in advance. The photograph brings immediacy - a captured instant - while the drawing unfolds slowly, through gesture and touch. When they meet, something unexpected happens, almost like two temporalities colliding and producing a third, unforeseen rhythm.

In that sense, these hybrid works are less about declaring a theoretical stance and more about opening a space of discovery - for myself and for the viewer. They may indeed blur the boundaries between technology and tradition, but I approach them as living experiments rather than statements. The surprise of the outcome is essential; it mirrors the unpredictability of life itself. If viewers are prompted to question what an image is, or where the line between the handmade and the mechanical lies, then that questioning is a welcome extension of the process. But for me, the heart of it remains the creative flow - the intuitive dialogue between pencil and lens that continuously reveals more than I had anticipated.

Much of your oeuvre foregrounds patterns and structures, whether architectural, organic, or digital, that might otherwise escape notice in the everyday. Could you discuss how this attentive gaze transforms the banal into the poetic, and whether you see your role as artist less in inventing than in revealing what is already latent within the visible world?

I have always been drawn to what usually escapes notice - the textures, structures, and patterns that hide in plain sight. When I walk through a city or travel, I don’t photograph monuments or wide vistas. Instead, I am compelled by details: the weave of a fabric on a table, the veins of a leaf, the shifting grain of stone, or the fragile inside of a fruit. By moving close, I let the camera transform the banal into something enigmatic. Suddenly the ordinary becomes a riddle - guess what this is - and in that moment of uncertainty, perception opens.

For me, art is less about inventing new realities than about revealing what is already latent in the visible world. A close-up dissolves familiarity and lets us see again, as if for the first time. What we thought we knew is defamiliarized, turned into poetry through attention. My role as an artist is to cultivate this gaze: to slow down, to notice, and to share the unexpected beauty that lives within the everyday.

In recent years, you have been featured in international biennales, art fairs, and critical publications, situating your work within a truly global conversation. How do you balance the universality of your themes, such as human–nature interconnection, with the specificity of cultural contexts, and do you feel that global circulation risks diluting, or instead amplifies, the singular voice of the artist?

What I value most about exhibiting internationally is the dialogue it creates: my works travel far beyond the moment and place of their making, and they encounter audiences with different cultural lenses. The themes I explore – human-nature interconnection, patterns of belonging, the fragile balance between estrangement and intimacy - are, in many ways, universal. They touch on experiences that are shared across cultures. At the same time, each context adds its own inflection: a viewer in Vienna/Austria may read the triptych with the algal bloom differently than a viewer by the Italian sea where I first found it. This multiplicity of interpretations enriches the work rather than diluting it.

Global circulation, for me, does not erase the singular voice of the artist; it amplifies it by allowing resonance in unexpected places. The specificity of my gaze - whether a close-up of a leaf’s structure or a pencil portrait inspired by theatre and dance - remains intact, but it meets new stories, new cultural narratives, and expands through them. I see this not as a loss of authenticity but as a widening of the conversation, a way for art to live many lives while still carrying the pulse of its origin.

Your declared aspiration to expand into sculpture suggests a desire to give spatial and tactile dimension to what has so far lived primarily on canvas, screen, or wall. How do you envision the translation of your visual language into three-dimensional form, and what possibilities for embodied interaction do you imagine sculpture might unlock that remain elusive in two-dimensional media?

It’s true that I have spoken of sculpture as a kind of next horizon for my practice. Until now my work has lived mostly on surfaces - paper, canvas, walls, screens. Sculpture feels like the moment when those surfaces might step into space, when the forms I draw or photograph could suddenly share the viewer’s physical environment. To me, that is both thrilling and intimidating. I haven’t yet engaged deeply with the medium, but I hope one day to be brave enough to do so.

What excites me about the idea is the possibility of embodied interaction: that a viewer could walk around a piece, sense its weight, its shadow, its tactility. In two-dimensional work, I can suggest rhythm or intimacy, but sculpture would allow the body to encounter art as another body in space. It would make the dialogue even more physical, even more immediate.

So for now, it remains an aspiration - something that hovers at the edge of my practice like an invitation. I see it not as abandoning my visual language, but as letting it grow limbs, volume, presence. Perhaps one day I’ll accept that invitation fully.

With major upcoming exhibitions at Insa Artcenter in Seoul this September and the Florence Biennale this October, both significant stages for contemporary dialogue, what dimensions of your practice are you most eager to share with these distinct audiences, and how do you anticipate these contexts will shape or expand the reception of your work?

What excited me most about exhibiting at the Identity show at Insa Artcenter in Seoul earlier this September was the chance to share how my work merges photography, drawing, and digital media. In Korea, with its traditions of calligraphy and innovation, I felt that this dialogue between tradition and technology resonated in a very particular way. The exchange with the audience there was invaluable, as it revealed new dimensions of my work through their perspectives.

Looking ahead to the Florence Biennale this October, with its theme Light and Darkness, I will present three digital artworks that merge photographs of humans in surreal, futuristic, almost out-of-space settings. Here, I hope to explore how the human form can become a vessel for both illumination and shadow, for vulnerability and transcendence. Florence, with its deep artistic history, offers a unique stage for this exploration. I anticipate that the context will amplify the dialogue in my work between tradition and the digital future, grounding the surreal in a lineage of figurative art while also opening it toward speculative, visionary horizons.

For me, exhibitions are never only about presenting finished works but about entering into a living exchange. Each context has the power to expand how my work is seen, to reveal aspects I may not have anticipated. That unpredictability is what makes showing art on a global stage so vital: it keeps the work alive, changing, and responsive to the world.