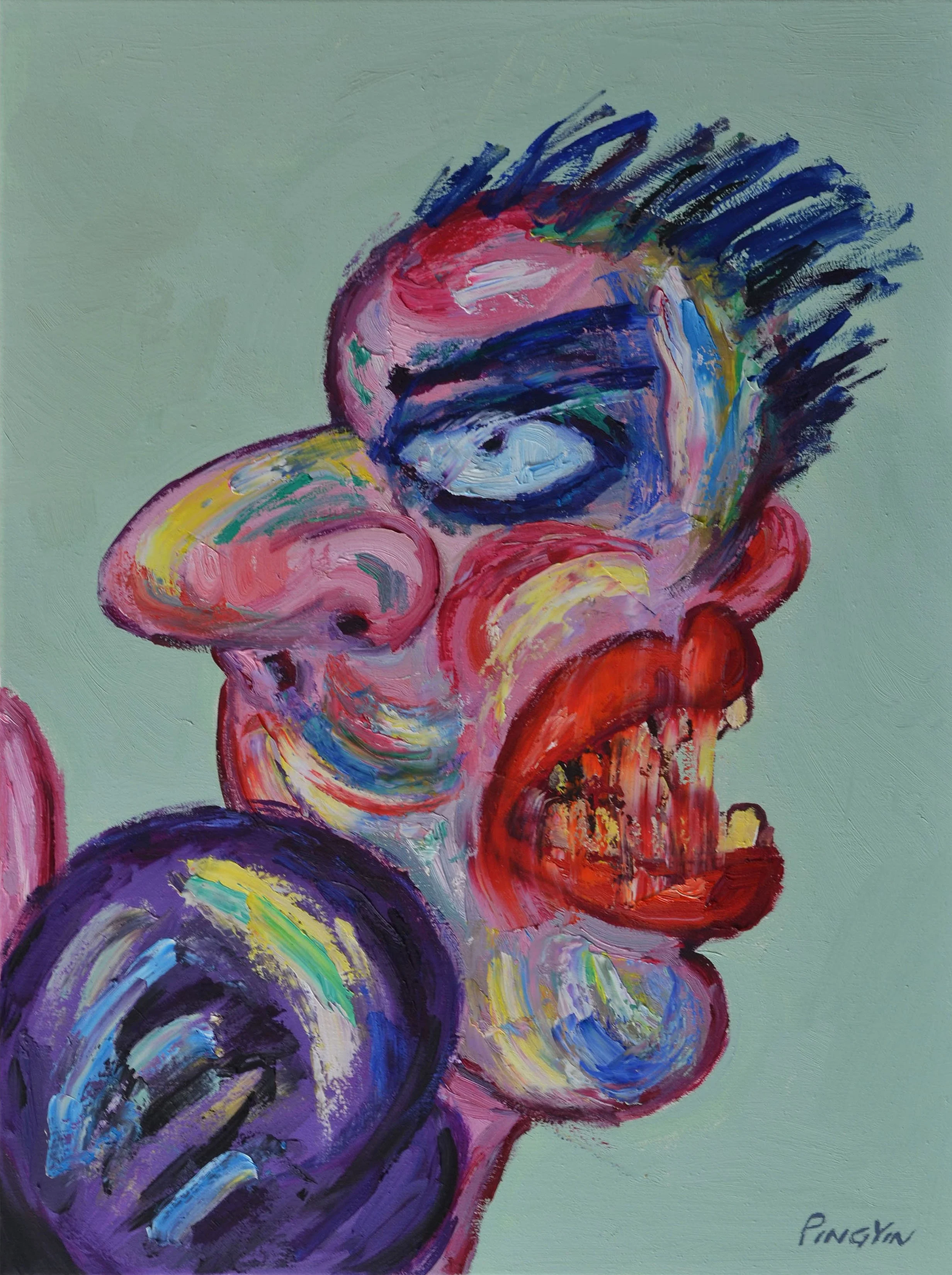

Ping Yin

Ping Yin was born in Beijing, China. In 1996 he emigrated to the US.

Ping paints primarily in oil and currently lives in New York City.

Ping started to paint at a very young age. In 1986 he finished Art college education in Beijing then became a professional artist working at the China Post Museum for several years.

Ping has been the winner of many important prizes in China. In1993 he created a major acrylic fresco for the Hilton Hotel in Beijing. He has had 4 solo exhibitions in Beijing and in New York, as well as joining many group shows internationally.

Ping Yin’s paintings have been in collections exhibited by the Beijing International Yiyuan Art Museum and the Tokyo Cunshang Art Museum.

Ping Yin likes to use bold colors and rough powerful brush strokes, Fighting is the theme of his recent paintings.

Your early years in Beijing coincided with one of the most ideologically rigid periods in China’s history, the Cultural Revolution, yet your first artistic epiphany came through forbidden Impressionist picture books you encountered at your teacher Luo Gongliu’s home. How did this act of quiet rebellion, this covert exposure to Western color theory and light, plant the psychological seeds for your lifelong obsession with luminosity? How do you reconcile that early defiance with the deeply internalized discipline of traditional Chinese painting?

I am a painter born in China, and my early growth and art education were all completed there. The first time I encountered Western art was when I saw some French Impressionist books at the home of my teacher, Professor Luo Gongliu, at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. This was during the Cultural Revolution, which was a time when Chinese culture was at its darkest and most closed-off period. When I saw these beautiful art books, I was deeply shocked, feeling a sense of freedom in art that was unimaginable to me—such beautiful works of art! Later, I majored in decorative design and ornamental painting at university, where I not only formally studied Western art, including drawing and oil painting, but also learned Chinese traditional ink painting and meticulous brushwork. The East and West are so different, yet both are equally great. I spent several years traveling through China, visiting places like Dunhuang, Yungang, and Longmen Grottoes, and the art there also deeply impressed me. So, I decided to take a path of blending Eastern and Western art. I created a series of works using acrylic paints and Chinese ink on rice paper, which absorbed the color concepts of Western art while retaining the charm of Eastern art. In 1992, I held my first solo exhibition in Beijing. Renowned Chinese art critic Liu Xiaochun hosted an academic seminar for me, where the works received societal recognition and praise. Western and Eastern art are so different, yet both equally great. Many Western artists, such as the Impressionists, were influenced by Eastern art, for example, the impact of Japanese ukiyo-e on Impressionist painters, which led to vibrant, life-filled artistic styles.

Your recent paintings confront the raw existential struggle of human beings in society, a terrain of inner and outer conflict rendered with aggressive brushwork and tormented expressions. In an era when much of contemporary art leans toward conceptual coolness or digital detachment, your work unapologetically re-centers the body in pain and the soul in anguish. What compels you to anchor your aesthetic in the ferocity of lived emotion? How do you see your expressionism situated within the lineage of both Western modernism and Chinese humanistic traditions?

In recent years, my painting style has shifted towards Expressionism, and I’ve created a series of works focused on the theme of struggle, featuring strong visual impact. The struggle I depict is the most fundamental state of human existence, even the survival law of the entire animal kingdom. The brutal killing, the weak being eaten by the strong, this is the most basic phenomenon in the world. When people come into this world, they must struggle to survive, and only through fighting can they progress. I often watch UFC fight videos, where muscular fighters brutalize each other, and this excites me, linking it to the brutal realities of society. I am eager to express these forces, this wildness, and this cruelty. I used the bold brushstrokes from Chinese ink painting and directly scraped oil paint onto the canvas with a palette knife. This is a direct release, creating an aesthetic and philosophical tension.

Having lived and worked extensively in both China and the United States, your oeuvre straddles a complex transnational identity. Can you speak to the aesthetic and philosophical tensions that arise when navigating the Western canon of oil painting through the lens of an Eastern artistic sensibility and vice versa? How has exile, voluntary or otherwise, sharpened your sense of visual language and the emotional urgency of your brushwork?

China and the United States are two completely different countries, with differences in history, culture, and societal systems. Chinese culture is grounded in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, while Western culture stems from Greek and Christian civilizations. Yet, there are many commonalities between the East and West, especially in the shared human experience—people all yearn for freedom, equality, and fraternity. Moving from China to the U.S. was a huge leap in my life, but I never felt out of place because, like many Chinese artists, I had great admiration and longing for Western art. In my first few years in New York, I came to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art every day, hungrily studying the works of the great masters, from Rembrandt to Monet to Van Gogh. It was truly a pleasure. I learned a lot from the masters, which had a great influence on my subsequent artistic development.

You once said that “color is the soul of painting.” In your American period, particularly in depictions of everyday serenity like lake scenes, sun-drenched beaches, or intimate restaurant interiors, there seems to be a luminous tenderness, almost a reverence, toward ordinary life. How does your treatment of color differ when expressing inner psychological war versus quotidian peace? Is color, for you, a weapon, a sanctuary, or something else entirely?

An artist’s life experiences shape their direction in art creation. Having lived in the U.S. for a long time, far from the Chinese environment, I lost the inspiration and desire to create works based on Chinese themes. I fully integrated into American life, going to bars with American friends, watching musicals together, participating in family gatherings, and traveling to Europe. All of this led me to feel a desire to paint American life scenes. The works of the Impressionist masters opened my eyes, especially the late French painter Pierre Bonnard, whose color handling fascinated me. His ability to perceive colors that ordinary people couldn’t see, and his vivid, subtle handling of light and color, made me realize that color is the soul of painting. In my works, I focus on depicting reflections on cutlery, ripples on a lake, and the dim lighting in restaurants. I try to express color in the most vivid and rich way possible. Color is indeed my weapon, and also my sanctuary.

Your early accolades in China were rooted in ink and wash, a medium steeped in spiritual minimalism and ethereal restraint, yet your mature practice in oil embraces maximalist saturation, thick textures, and brutalist figuration. What catalyzed this transformation from the delicate lyricism of traditional Chinese media to the muscular intensity of oil-based expressionism? Was this evolution aesthetic, philosophical, or perhaps even biographical?

Chinese ink painting is grounded in Taoist transcendence philosophy, reflecting spiritual minimalism and ethereal beauty. However, my artistic creation has never developed in that direction. My early ink works combined Western modernist compositions and Western painting color concepts, so they were not traditional Chinese ink paintings. I used both ink and acrylic paints on rice paper, focusing on rich and saturated colors, and I liked using thick paint with rough brushstrokes, creating a coarse texture on the surface of the painting. Among Western masters, I preferred Michelangelo's works over Raphael's, I preferred Delacroix’s works over Ingres‘s. I favored grand, bold, and courageous works, which aligns with my own temperament and personality. In my recent Expressionist works, I emphasize bold and unconstrained brushwork and large-scale color application.

In your expressionist portraits, you seem to deny beauty in the classical sense, embracing instead the sublime grotesque, the furrowed brow, the clenched jaw, the howling mouth. These are faces not composed for admiration but for confrontation. What do these visages represent to you? Are they archetypes of collective trauma, symbols of spiritual resistance, or mirrors of the human condition as you’ve encountered it in diaspora?

In this series of Expressionist portraits, I titled them “Punching Face.” The figures are grotesque, twisted, almost mad, creating a strong visual shock. This contrasts sharply with the classical notion of beauty. I admire classical beauty but also embrace modernist grotesqueness and madness. It’s the crazed reality of the world that drives people insane—this world is filled with sin, war, deception, pain, and injustice. These portraits reflect the inner suffering and struggle of modern individuals.

Your works often blur the line between Impressionistic lyricism and Expressionist drama, two movements traditionally positioned at stylistic and emotional opposites. How do you conceptually and technically reconcile the ephemeral shimmer of Monet’s atmosphere with the existential depth of Van Gogh’s psychological brushwork? Is this duality a conscious methodology, or does it emerge organically through your intuitive response to light and emotion?

Impressionism and Expressionism are very different. My works in the Impressionist style were created before 2018. After 2018, my style shifted toward Expressionism, and I created many works on the theme of struggle. I feel that these recent works better reflect my inner state. My inner world no longer leans toward the gentle lyricism of Impressionism, but instead embraces cynicism and wildness. I no longer enjoy the graceful beauty of Impressionism but prefer the rawness and tension of Expressionism. Impressionism expresses the beauty of the real world’s colors and light, making one feel relaxed and joyful, while Expressionism conveys the intense, painful, and struggling emotions within people’s hearts, which can touch one’s soul in a deeper, more oppressive way.

You’ve stated that “to live is to fight to live,” a potent aphorism that recurs throughout your thematic practice. In a contemporary art world increasingly preoccupied with irony, identity, and digital culture, what role does the metaphor of struggle, raw, physical, emotional, still play? Can art still speak to the ancient, even mythic battle for survival and meaning without descending into cliché or sentimentality?

Life itself is a struggle, a-battle,with different goals at different times.Only through hard work can one become strong and defeat one’s opponents, otherwise, one will be eliminated in the cruel reality of the world. This world has never ceased war, oppression, and resistance. My works, based on themes of struggle, metaphorically represent this world’s most fundamental phenomena and reflect the struggles of people in real life. I like to emphasize people’s ugly faces and expressions of pain and struggle. Within those exaggeratedly developed male muscles, boiling blood flows, fierce hand-to-hand combat, and brutal strangulation --this is a hymn to the courage and strength of life.

Your series depicting American life, whether scenes of summer leisure, country music performances, or reflective dining moments, carries a poignancy often absent from realist genre painting. Beneath the chromatic beauty lies a quiet intensity, a whisper of alienation or longing. As an immigrant artist, do you view these works as documentation, assimilation, or gentle critique? And how does your outsider perspective sharpen your aesthetic sensitivity to what others might overlook?

Having lived in the United States for so long, I’ve completely immersed myself in American life. These works reflect my personal experiences there. I’ve gone on beach vacations-with American friends, attended concerts, attended weddings, and even visited bars. In their various scenes, I’ve felt the beauty of color, light and shadow. The inspiration for these creations comes naturally, driven primarily by intuition and my study and understanding of Impressionism.

You’ve been collected by institutions in both East Asia and the West and recognized by intellectual circles such as the “International Who’s Who,”yet your works often speak to profoundly anti-institutional themes: the brutality of existence, the isolation of the soul, the grotesque beauty of suffering. Do you see your work as a challenge to institutional narratives of beauty, success, or humanism? And how do you navigate the contradiction between critical acclaim and the deeply personal, even private, origins of your artistic drive?

I believe that a true artist shouldn’t worry about what art critics say,but should instead create according to their own soul. My work has indeed been acclaimed by both Eastern and Western art circles and has won numerous awards, but this doesn’t stop me from exploring new territory and expressing new themes. An artist’s work is only valuable if it expresses their inner truth, and truth will always triumph over falsehood. Goya created many beautiful works throughout his life, but in his later years he also created horrific works such as demons devouring people and executions, and these works are equally great.