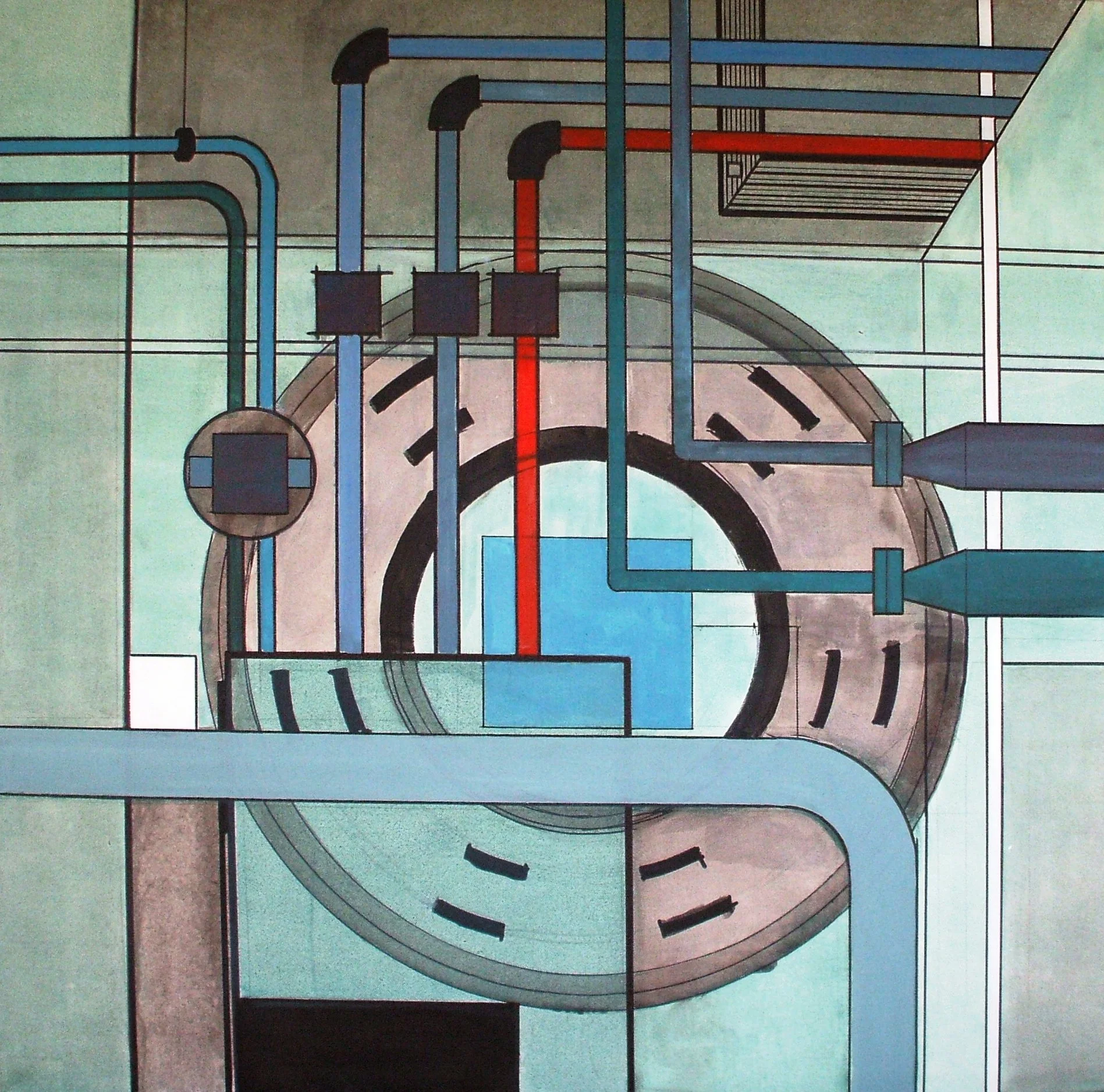

Giovanni Tozzetti

Giovanni Tozzetti was born in Rome, Italy (1933) into a family with very deep roots in the Arts. His grandfather and two of his uncles were well known sculptors in Italy: the Fiordigiglio family. He studied drawing and sculpture in his childhood under the guidance of his uncle Vincenzo in Atelier of via Margutta, Rome. He has studied at the Scuola Statale delle Arti (National College of Arts) in Via Gesu’e Maria which further enriched and ultimately completed his academical mastering in fine arts. As his life progressed, his interests switched to more practical applications. He undertook study of mechanical engineering where a passion for industrial design was fomented. Leading on from this, he then proceeded to work for many years with various local and International engineering teams.

Giovanni, you once said you aim to interpret stories in a way that reveals their beauty or value, without obscurity. In an age where conceptual ambiguity often dominates contemporary art, how do you maintain clarity of message without sacrificing poetic depth?

I try to limit the design of the work so that only essential elements are represented. This helps remove ambiguity from the story I am trying to portray and helps preserve its consistency.

Your early formation took place in the ateliers of Via Margutta under your sculptor uncle Vincenzo—one can almost imagine the air thick with classical discipline and creative fervour. How has this Roman foundation continued to shape your aesthetic decisions across vastly different cultural contexts, from Italy to Australia to the Philippines?

I still rely heavily on that foundational knowledge, even today, and my aesthetic decisions are still rooted in those classical disciplines. I definitely appreciate and value the differences in each of these cultural contexts and the new ideas or perspectives they can bring forth, but they haven’t changed the Roman fundamentals of how I implement my work.

As an artist-engineer, you possess an unusual dual fluency in technical precision and expressive abstraction. How does this duality manifest in your artistic process, and do you ever find tension—or unexpected harmony—between these two modes of thinking?

I find these areas draw on uniquely different types of knowledge, skillsets and tools and I have found that tension between these two modes of operation is not as common as one would expect. I have my computer for my technical work and my pencils and brushes for figurative and abstract work and it is boundaries like this that allow me to settle into the correct frame of mind for a given task.

Your trajectory navigates classical training, industrial design, and digital tools. Do you view technology as an evolution of traditional craftsmanship, or does it require an entirely new creative philosophy?

Technology is just an evolution upon the traditional techniques artists have used to express their ideas to the world. New technology provides us with greater breadth and depth in which we can communicate ourselves to others.

In curating community-driven exhibitions and founding arts organizations, you've shaped not only works but also platforms for artistic exchange. What responsibilities do you believe artists hold within their communities, especially in multicultural societies like Australia?

I believe it is important for artists to share knowledge of their craft and offer their perspectives to members of the community. It is through this sharing that we strengthen our bonds with family, friends and neighbours and it provides an important thread, amongst the many that exist, that help weave that sense of community amongst a group of people. Differences of perspective should be appreciated and used as an opportunity to learn more about a particular person, subject or area. When people feel seen and understood, wonderful things can be allowed to flourish.

From the sculptural legacy of your Fiordigiglio lineage to your cross-disciplinary oeuvre, how do you perceive the role of heritage in sustaining or challenging the artist’s identity?

Whether it’s considered a direct challenge to the idea of heritage and the role it plays or not, I think a key part of being an artist is showing the world how you, as an individual, see and interpret things. The physical creation of the art is just the medium, window or language in which you communicate that interpretation to the world. The work should be original, thought provoking and be focused on speaking to the concept you are trying to portray. This a key component of defining your own identity as an artist - it does not matter whether you have family history in the arts or not.

The narrative arc of your work spans continents and decades—Rome, Sydney, Limassol, Nowra. Do you think the notion of 'place' functions as an anchor in your work, or has your art become more about dislocation and hybridity

I don’t believe ‘place’ has shaped the trajectory of my work as much as the experiences and people I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with throughout my life. People and experiences are what has helped me mature and grow my perspectives as an artist - be they from the creative powerhouse of Rome or the small (but beautiful) city of Nowra.

Your artworks often eschew theoretical opacity in favour of accessible storytelling. How do you engage with contemporary critics or curators who privilege concept over craftsmanship, or abstraction over narrative?

I’ve always let my inspiration guide me in my work and I don’t normally think about critical judgements or which ‘way’ of communicating a narrative is more appropriate. I like more direct storytelling in my work, but that doesn’t mean critics who favour concepts or abstractions are wrong. It’s just a different way of telling a story and should be celebrated as such. That is how I approach any such discourse with my peers.

Given your lifelong engagement with both art and technology—and your lectures on this intersection—how do you envision the next generation of artists navigating this dual terrain?

I believe that the next generation of artists will see technology as an extension of the traditional tools of brushes, pencils and sculpting instruments that I’ve learnt to work with. Those who have had access to these new tools in their formative years will naturally become very good at using them to express themselves. Over time, just like I have, they will have opportunities to mature into different disciplines that each have their own tools to learn. I think the next generation of artists are well positioned to navigate these new horizons with more elegance and nuance than we’ve seen in the past.

After decades of creation, exhibition, and community advocacy, what does artistic success mean to you now, and has that definition changed since your early days in Via Gesù e Maria?

For most of my life I’ve always wanted to be an artist. You could say, given my family background, it was almost pre-determined. My uncle imparted the knowledge, techniques and perspectives I needed in order to begin my journey with a steady foundation and my career in mechanical engineering provided me with the means to live a decent life. These two crucial elements allowed me to create, paint, sculpt and pursue without limitation. My work followed my natural inspirations and I did not have to worry about whether my artworks were sellable in order to pay the bills. They stayed true to my original visions and were produced without consideration towards financial value. This is the essence of artistic success – being able to tell your story in its original form without interference or manipulation and have people listen, and my understanding of this definition has not changed, even from my early days as a budding artist.