Yasmina Barbet

Website: https://www.yasmina-barbet.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/yasmina.barbet

Yasmina Barbet, is a French photographer trained at the IED in Rome, developed in Paris a visual approach enriched by drawing, art history, and image processing. Upon returning to Rome, she created a personal online photographic archive in 2008.

Since 2009, she has begun a collaboration with Wostok Press, covering major events such as the Vatican and the festivals of Venice and Rome. She has published several works, including Sénégal Natangué, presented at the Italian Senate.

Winner of the 2nd "Lorenzo il Magnifico" prize at the 2025 Florence Biennale, and 3rd in 2017, her work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions across Europe and the United States.

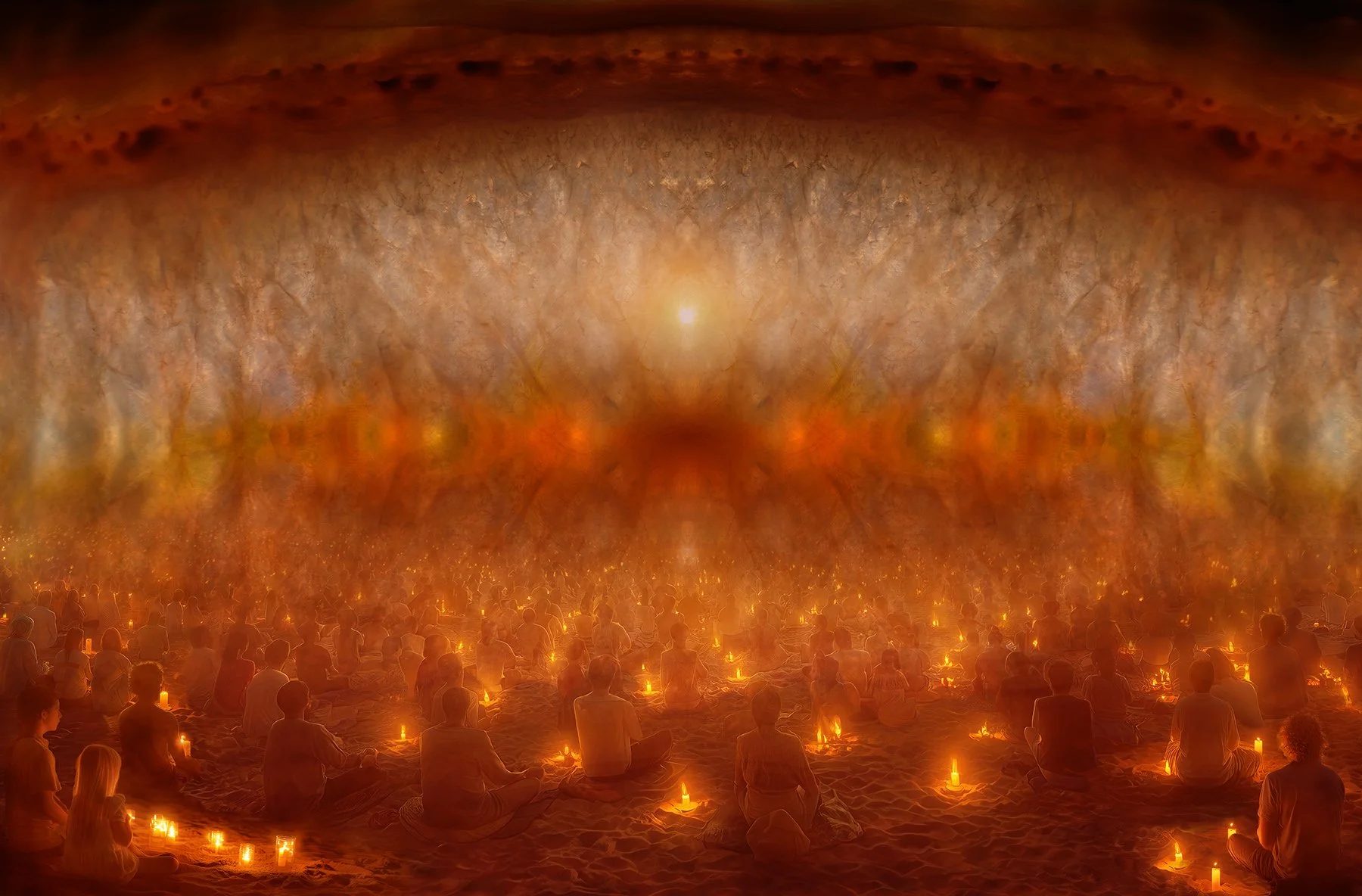

She engages in imaginal research that explores the emotional nuances of the psyche and the inner states we experience, sometimes drawing on mythology—a profound and timeless mirror of the human soul.

She merges her own photography with digital techniques, creating an introspective and contemporary visual universe.

Yasmina, your works often fluidly oscillate between mythological references and deeply personal states of mind, as if mythology becomes a mirror of our inner life. How do you decide that a myth—like Pygmalion and Galatea or Icarus—is the most appropriate symbolic language to express the emotional and spiritual states you wish to capture?

This exploration was born from a deep desire to delve into the depths of the human psyche—our emotions and states of being. Mythology, as a universal symbolic language, offers a rich and timeless framework. Myths and their archetypes provide fertile ground upon which I can build a narrative structure for feelings that are often ineffable. When I sought to evoke a form of platonic love, I turned to the story of Pygmalion and Galatea—a tale both delicate and unsettling that aptly embodies the depth of that sentiment.

In your artistic approach, you describe images as a true language connecting rational meaning to inner experience. Could you elaborate on your perception of photography as a spiritual practice—a bridge between body, heart, intuition, and thought, almost like a form of meditation or prayer?

My images emerge in several stages. I begin by preparing what I call my “backgrounds”: a base of medium-format macrophotography that serves as a visual archive I draw from later. Then comes the research phase—an intense, charged period where all aspects of being converge: heart, experience, intellect, intuition, memory. It’s a vivid, rapid stage, like sketches thrown onto paper, feverish drafts. Sometimes you find something; sometimes you don’t. Finally, I transform the initial impulse into a more accomplished image. It’s an alchemist’s work: I measure, refine, transmute. This slower, more meditative phase is often accompanied by music and requires patience, attention, presence…

Your process transforms reality into allegory, allowing natural or human elements to take on symbolic meaning. To what extent are you conscious of this translation while working? Do you start with a clear symbolic intention, or does symbolic depth emerge naturally as the layers of your images unfold?

As mentioned earlier, I use my “backgrounds” symbolically: through their chromaticism, vibration, energy, and texture, they represent an emotional state—an inner dimension. It’s within this space that I immerse my subject, which in turn affirms the emotion or state of mind I seek to express. Sometimes I begin with a background that inspires an image; other times, with the subject itself. I have a particular affinity for allegory and use it occasionally, as it feels like a just and powerful way to convey certain messages.

Having lived in Italy and France—two places where art, spirituality, and cultural memory are deeply intertwined—how has the spiritual atmosphere of these environments influenced your artistic sensitivity, especially in your ongoing dialogue between mythology and the human psyche?

I’m incredibly fortunate to have been born between two cultures and two magnificent countries: France and Italy. France introduced me to art very early. At six years old, I discovered Van Gogh and Seurat, whose paintings awakened a deep resonance within me. Later, Klimt, Gustave Moreau, Monet, Rembrandt, and Vieira da Silva left lasting impressions. Their styles—ranging from symbolism to baroque to abstraction—all carry, in my view, a strong spiritual imprint. Each left an enduring trace.

Italy, on the other hand, embodies creativity in its most radiant form. There, art is not only contemplated—it is lived. It’s a country of a thousand wonders, where discovery, awe, and vibrancy never cease.

The myth of Icarus in your work Too Much Light of Icarus radiates both the ecstasy of transcendence and the tragedy of destruction. Do you believe that, in art as in life, spiritual illumination always carries the risk of burning too close to the divine? Is this tension something you intentionally integrate into your work?

To me, the figure of Icarus embodies a deeply human passion: that naïve impulse toward the absolute, toward light—marked by pride, burning desire, and an irrepressible thirst to push beyond the limits of possibility. I feel great compassion for Icarus.

Spirituality, by contrast, seems to me an introspective path that requires endurance and patience—a slow, silent quest which, rather than defying the laws of the world, seeks to transform wounds into light and to expand consciousness. One might say that Icarus’s passion is an ascent driven by desire, while spirituality is an elevation through the depths of being. Two upward movements: one consumes, the other illuminates.

In The Secret, the layered blue textures suggest silence, concealment, and perhaps an inner depth that is difficult to express. How do you approach the theme of secrecy or the unspoken in your images, and do you believe photography can reveal spiritual truths that language cannot?

Thank you for mentioning this image. It belongs to my earliest creative impulses—I was in my twenties. If you linger on the face, you’ll notice, just above the forehead, a subtle opening, like an invisible door. It seems to open onto a space of consciousness that cannot be grasped or fully contemplated, only sensed. Artists have always embedded enigmas and messages in their works—fragments of veiled truth. For me, it’s not about fixed answers, but intimate questions. Questions I entrust to the image and sometimes offer to the viewer, so they may find their own resonances.

Spirituality often involves a search for connection—with the divine, with others, or with our deeper selves. In your mythology-inspired series, do you see your work as a universal bridge between time and cultures, or as an intimate exploration of your personal journey marked by faith, doubt, and wonder?

“There is no such thing as love, only proofs of love,” wrote Pierre Reverdy. Similarly, spirituality is not, for me, an abstract idea but a path of elevation—an expansion of the soul, a constant attempt to anchor it in reality. It manifests in presence, in exchange, in creation... Even when my images draw from mythology, they remain above all an expression of an inner journey, traversed by faith, doubt, and wonder. Robert Delaunay said: “The artist begins the canvas, but it is the viewer who completes it.” Thus, the observer, with their own path, finishes or reveals the image in their own way. The work then becomes a bridge between the artist’s inner world and that of the one who contemplates it.

You’ve worked in both documentary contexts—press agency reporting—and in allegorical and symbolic photography. How do you reconcile these two seemingly opposite practices, one rooted in external truth and the other in inner or spiritual truth? Do you see them as distinct or as part of a continuum of image-making?

The experience of reportage was incredibly enriching. My agency director was a mentor, a coach, and a friend. He pushed us to exceed our limits as photographers. I lived through incredible moments. As I’ve mentioned before regarding the creative moment, reportage is similar: heart, experience, intellect, intuition, and knowledge merge to better convey the reality around us. The difference is that we are immersed in a real-life scene, in which we compose. Everything then depends on one axis: the positioning of our body, our eye, and the camera.

Reportage teaches us to live fully in the moment. We become truly aware of the ephemeral, and carpe diem becomes our credo.

In a contemporary art world often dominated by irony, critique, and technological experimentation, your work emphasizes poetry, symbolism, and spirituality. What do you hope to bring to contemporary audiences through your art? Do you see it as an antidote, a reminder, or perhaps an opening toward a deeper vision of existence?

It’s wonderful that there are so many ways to express art, and that it is so rich and varied. For me, it’s not an intellectual choice. What one perceives is only the visible tip of a long inner journey—like the tip of an iceberg—a personal reflection composed of fragments of consciousness and experience. I have no premeditated intention toward the viewer. A friend once told me that art and culture are ways to journey through existence a little less alone. So, if someone, while looking at one of my images, feels understood, feels a little less alone, I would be deeply moved.