Ursa Schoepper

Ursa Schoepper first completed her studies in Natural Science with state examination. In addition she completed a study in cultural management, state examinaten, with a concentration in fine arts, new media at Prof. Dr. Eckart Pankoke, Prof. Dr. Ulrich Krempel, Prof Dr. Michael Bockemühl. In her Agentur für Virtuelle Denkraeume she was working as a cultural manager. As a cultural manager responsible for the conception and realization of various projects in the field of cultural education systems. In 2001 she was awarded the Media Promotion Prize of the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia for „Das Museum der abwesenden Bilder“. Since 2003 Ursa Schöpper has been working primarily as a photographic artist. Her artwork has been exhibited internationally and she is the recipient of notable awards.

Ursa, your work repeatedly positions photography not as a medium of representation but as a conceptual and perceptual laboratory. How do you articulate this shift from depiction to transformation, and in what ways does your practice redefine the ontology of the photographic image as a structure of thought rather than a trace of reality?

Due to its mathematical and physical systems, the digital image enables the simulation of reality. The visible gives the imagination a foundation that can initiate thought processes beyond mere perception. Like any image, a digital image initially depicts a visible, imaginary object. Furthermore, it allows us to show what we imagine about it. For example, if the image shows a tree, we can depict how the tree transforms and seemingly directs our gaze toward ice floes. Digital images can be tools for constructing imaginary images.

You describe digital photography as a convergence of light image and data image, a hybrid entity operating between the sensory and the computational. How does this dual nature inform your visual language, and how do you navigate the tension between algorithmic logic and intuitive imagination in the construction of your works?

A prerequisite for my creative process was a thorough understanding of the mathematical and physical systems of a digital camera and a computer; knowing that each point of light is stored as a color value, knowing that a computer's graphics program possesses the same linguistic grammar as a digital camera. This allows me to use my imagination with an image I have taken, in order to arrive at a new, freely chosen visual statement through transformation. The digital photograph is both a template and an amplifier of my imagination.

Your artistic trajectory moves from natural sciences to cultural management and finally into experimental photography. How do these disciplinary crossings shape your understanding of artistic production as a form of research, and do you consider your studio a site of inquiry comparable to a laboratory?

My studio was indeed initially a place of investigation. I experimented with light and prisms. Mathematically, I tried to access the digital, algorithmic structures through high magnification and interpolation. As my understanding of these processes deepened, and as some structures reminded me of familiar patterns from other disciplines, I began to examine these systems of order more closely. My biology studies offered many points of entry, for example, when I recalled illustrations of single-celled organisms. Furthermore, nature, with its systems of order and interactions, provided numerous examples. Meantime my attention is also drawn to cultural and societal contexts, such as questions concerning our environment. In a solo exhibition during the 61st Venice Biennale, July 2026 at Palazzo Pisani-Revedin (Palazzo Rossini) for example, I will present artworks on the theme "The individual in the face of nature".

In your statements, you often evoke the idea of an “inner order” of digital photography. Could you elaborate on this notion, and how does your practice attempt to reveal or reconstruct this hidden structural logic within the image?

Photography is, first and foremost, a light-drawn image of a world existing outside our consciousness. Experimental, computer-aided photographic art is a networked art form with aesthetic elements of physical-mathematical, logical, and technical origin. Through precise calculations, it is initially possible to accurately delineate forms and colors, surface texture, light and shadow relationships, perspective, and other properties of the image. Initially, the static visual properties of the representation—its pixel surface—correspond to those of the object it depicts. Its image initially has the same geometric form, the same color nuances, and the same interplay of light and shadow. When the colors and the respective light intensity of pixels are subject to a specific order, our visual perception no longer considers them individual, adjacent points of light, but rather the emergence of an underlying whole, a perceived unity. It is, in fact, our perception that brings the object into being. In my photographic art, there is a conscious and proactive integration of technology into the creative process, not as an aid, but as a generative force. Realistic reality gives way to the calculated, to imagination, which then becomes realistic reality. The camera loses its character as an objective recording device of factual truths.

The idea of transformation appears as a central metaphor throughout your work. How do you conceptualize transformation not merely as a visual effect, but as a philosophical principle, and how does this idea relate to broader questions of perception, reality, and possibility?

A transformation initially implies a technical conversion. This photographic artwork, created through this conversion, is no longer a mere depiction of a fleeting moment of perception, but rather a sensory representation of a possibility inherent in the photographic material, thus allowing for a new and different perspective on photographic reproduction.The symbolic meaning shows a not-yet, something that is potentially existing within the sensually actual.

Your work has been associated with the legacies of Dada, Surrealism, and Constructivism. In what ways do you see your practice as extending these historical avant garde experiments, and how do you translate their spirit of disruption and reinvention into the language of digital photography?

Artists of the historical avant-garde sought, among other things, answers to the impending reorganization of existing society through their renewal of conventional imagery. It was a radical liberation, a liberation from concepts of form and color, a development of a higher, universal language. However, they also distanced themselves from the concrete imitation of nature. Arp, for example, did not want to abstract from anything. The aim was not to depict, but to shape. My free, abstracting approach to digital photography considers it as an archetype, as a substantial model of an imaginary reality. This new mode of representation does not present the visible as a mere view or perspective, but as a penetration, as a virtual visual possibility.

You have described the photographic artist as both composer and conductor. Could you expand on this musical analogy, and how does the logic of rhythm, tempo, and harmony influence the orchestration of visual elements in your digital compositions?

A composer is a person who creates musical works by structuring melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. The compositions in my photographic artworks are constructs that assemble a complete image from diverse elements; they are performances of interconnected content. To clarify these connections: The perceived music corresponds to the image. The score of a symphony can be compared to its digital representation. The notes of the score can be accentuated differently, and individual passages can be emphasized for specific instruments. In this way, a new piece of music can be created based on the score. Individual image elements can be rearranged, similar to the choreography of a dance. In this case, the artist is both composer and conductor. The irrational, the virtual, is inherent in all that is real. One simply has to uncover it.

The “Museum of Absent Images,” which you conceived as a social network in 2001, suggests a deep interest in immateriality and virtuality long before such concerns became widespread. How do you reflect on that project today, and how does it anticipate your current exploration of photography as a virtual and conceptual medium?

In implementing this project, my primary goal was to help young people learn to use new technologies independently and freely. A prerequisite was also learning to be free from ingrained patterns of experience with traditional media. The concept of the absent image quickly emerged as a metaphor. What can absent images be, and how can they be made visible? Digital photography, with its mathematical and technical systems, allows these questions to be explored anew. In the context of and interaction with AI, it is becoming increasingly clear how important it is, alongside technical understanding, to experience and learn to utilize one's own imagination and creativity in order to generate innovative ideas.

In an era saturated with instantly legible and hyper-documented images, your works often resist immediate interpretation. Do you see ambiguity as an ethical or political gesture, a strategy to slow down perception and invite deeper reflection?

Yes, that's an opportunity. Viewers of my photographic artworks confirm this. The works gain intensity through a strong reduction. They provide space and allow for an active, self-directed dialogue with the artwork. Art doesn't aim to dictate judgments or offer formulas; rather, it seeks to be perceived.

Your writings frequently invoke philosophers such as Flusser, Adorno, and Bloch. How do these theoretical frameworks enter your practice, and at what point does philosophical reflection transform into visual form?

As soon as I can view machines, such as the computer, as tools and not as partners acting autonomously without my input, I fundamentally rethink the digital imagery before me. What possibilities, what opportunities do I have to work artistically with these other technologically based objects? As an artist, I am in a constant process of perception and reflection. I don't remain statically. To think that if something is, can be changed, then what is, is not all there is, as Adorno said. It can inspire us to look for other, including virtual, possibilities.

You speak of experimental photography as a “metaphor of change.” What kinds of social, ecological, or existential transformations do you feel your work responds to, and how does abstraction function as a vehicle for such concerns?

Experimental, computer-generated photography produces calculable representations of visible objects. The result is imaginary. The image texture reveals that space and object value can be dissolved. This leads to a multifaceted fragmentation of form. Due to its algorithmic structure, experimental digital photography offers a new artistic formulation. This also means a reassembly of fragmented, culturally and communicatively connoted signs. Deconstructivist activities enable novel dimensions of content. It is possible to draw analogies to destruction through war or environmental damage. However, it is also possible to refer to natural processes that, within their context, exhibit similar hierarchical patterns to those we experience in our society. Nature for example knows diversity, a coexistence and interaction in constant decay and renewal. Its annual rhythms demonstrate how we traverse the path of life, sometimes torn apart, sometimes trapped in our own private cosmos. Nature knows displacement and hierarchical orders. The vibrant diversity of nature, its aesthetic appearance, its creation and decay, could be a reflection of a pluralistic society.

Many of your works appear visually minimal yet conceptually complex. How do you negotiate the relationship between formal reduction and conceptual density, and what role does restraint play in your aesthetic decisions? Your background in biology and your fascination with microscopic structures seem to resonate with the internal architectures visible in your images. How does the scientific gaze inform your artistic perception, and do you see parallels between cellular structures and digital image systems? You often describe the creative process as a reordering rather than a destruction of the visible world. Could you elaborate on this distinction, and how does the idea of reconfiguration shape your approach to photographic material?

Through my biology studies, I learned that even the smallest, simplest organisms can form highly complex systems. This reduction and simultaneous functionality fascinated me. Cell structures are independent, autonomous organisms. Image systems are created collages that, like phantoms of light, carry an artistic vision, while simultaneously functioning as dynamically constructive systems of force. For example, images of a dance choreography always show new figures that are interpreted differently from their predecessors. As an artist working with digital photography, I find myself in a constantly evolving process.

The digital image is frequently understood as infinitely reproducible and immaterial. How do you address questions of materiality, presence, and aura within a medium that is fundamentally based on data and code? You emphasize the importance of breaking perceptual routines. What kinds of visual habits do you believe contemporary viewers are most trapped within, and how does your work attempt to unsettle or expand these ingrained ways of seeing?

It is not photography that represents art, but rather the artistic idea expressed within it. The intellectual artistic activity, as a concerted action, does not have a result, but is the result itself. An experimental digital photographic artwork can reveal how manipulative interventions create visual statements that serve a specific purpose, even though a work of art itself is always purposeless. Art is the foreshadowing of an idea in the sensory realm. My photographic artworks are generally unique pieces. From the initial idea to the selection of the image section, to the transformation, and ultimately to the choice of the image carrier, there are many artistic considerations and steps involved. In this way, I consciously oppose arbitrary reproducibility. I thus attempt to give the artwork its own unique character, its own aura.

The metaphor of the virtual studio suggests a space that is both real and imagined. How do you understand the role of the studio in your practice, and does it function more as a physical environment, a conceptual framework, or a digital field of possibilities?

For me, physical space is important for carrying out experimental setups, for example, as is virtual space, which offers me the opportunity to realize what I've conceptually envisioned. In physical space, for instance, lighting setups are possible, and their images can serve as models. I also experimented with prisms. The digital, photographic result, made visible on the computer, then allows me, for example, to follow my artistic idea in virtual space by means of enlargements of partial views or by means of sine curves.

In your practice, the image is not a fixed endpoint but part of an ongoing process. How important is the notion of temporality in your work, and do you see each image as a provisional state within a larger continuum of transformation?

For me, digital photography is a model, an archetype, a preliminary representation of my world as it is perceived, fragmentarily, outside my conscious awareness. Understanding its internal technical structure allows me to create a work of art based on an idea, which I define as authentic and unique. My wish is that this work, viewed historically, retains its unique aura, that is, it is timeless. I don't see this timelessness in my digital photography itself, but rather in my digitally based photographic artwork. A digital photographic documentary image is, for me, primarily technical material. My creativity and ideas are limitless when it comes to creating autonomous photographic artworks.

You have spoken about the tension between the “either/or” logic of digital systems and the “both/and” logic of creativity. How does this philosophical opposition manifest itself in your working methods, and what strategies do you use to maintain artistic openness within technologically determined structures?

My artistic approach is a "both/and" approach, which aims to deal freely and independently with the resources available to it. Despite their inherent logic of "either/or," digital systems offer ample scope for playful interaction through combinations of individual systems.

As experimental photography continues to evolve in an age of automation, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic image production, how do you envision the role of the conceptual photographic artist, and what forms of critical or poetic resistance might still be possible within increasingly automated visual cultures?

I am a positive, solution-oriented person. The head, also my head, is still there for thinking.Let's use it and keep in Dialog to each other. Let's negotiate with each other what is good for us and our souls. As a photographic artist, I want to be able to provide inspiration.

Creative force and artistic ideas are not calculated. AI does not calculate according to meaningful structures but considers probabilities. The potential uses and dangers of AI should remain responsibly controlled by humans. It was and is humans who developed these systems.

https://www.virtuelledenkraeume.de

https://artitious.com/artworks/

ART MARKET EXPERTS 2026

https://www.artsper.com/de/zeitgenossische-kunstwerke?query=ursa%20schoepper

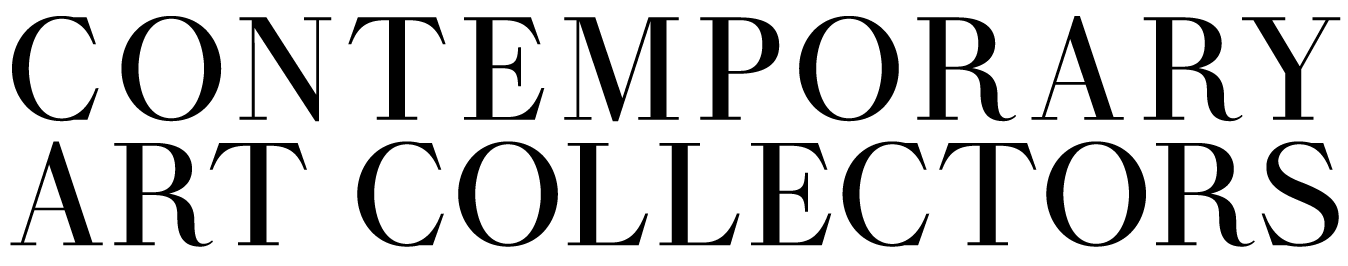

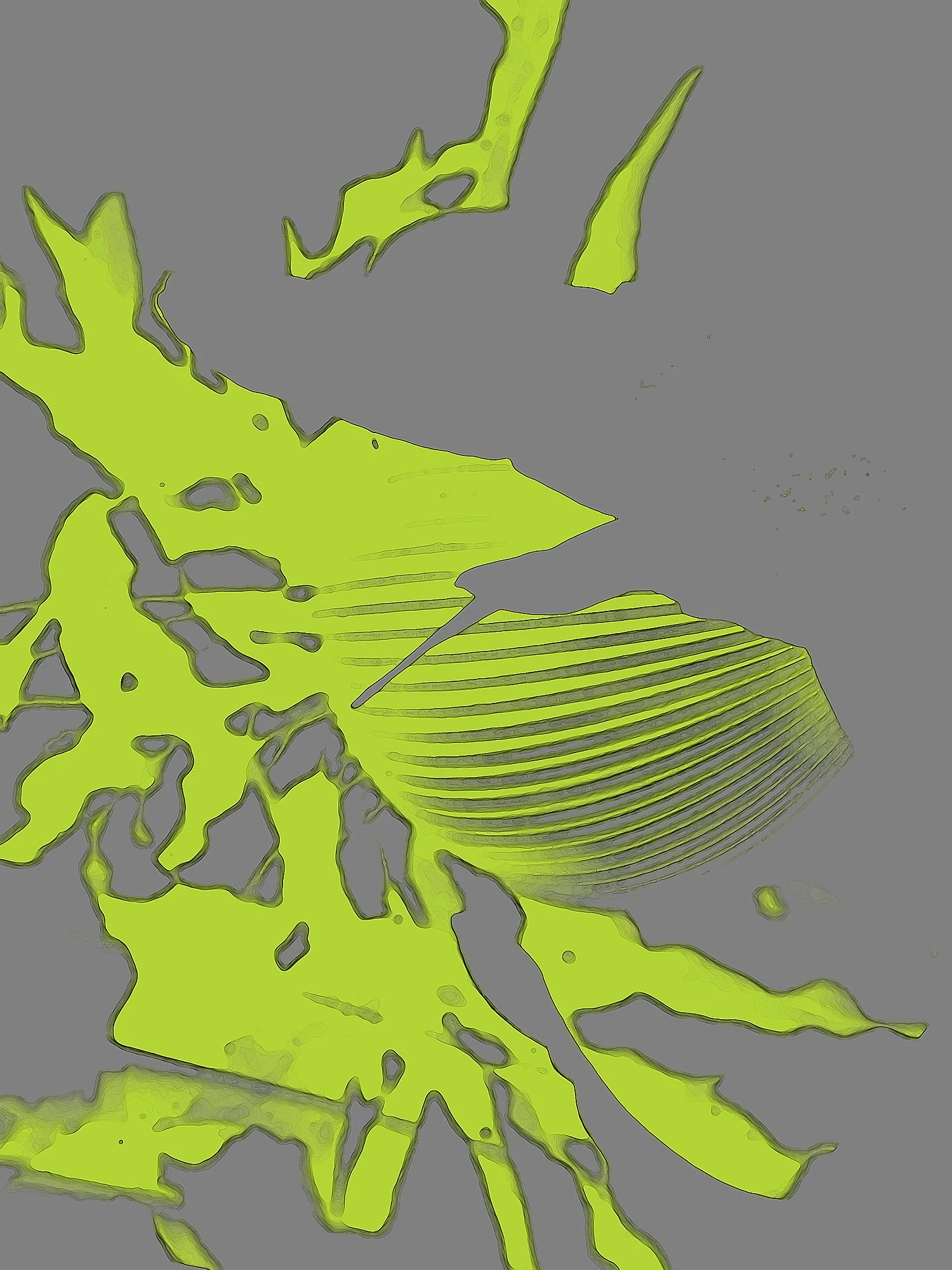

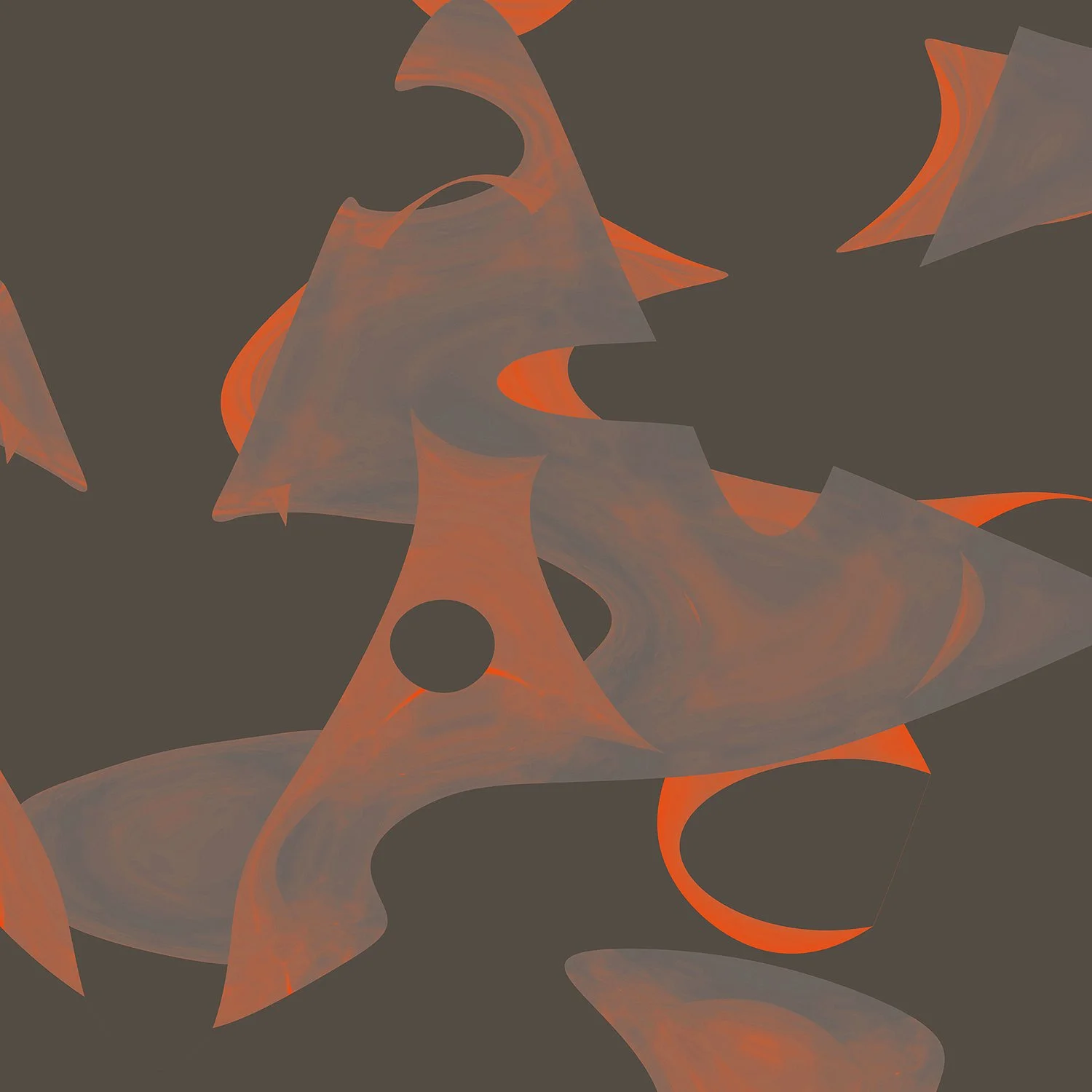

ursa_schoepper_mutation_of_a_plant, 2025, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 80 cm, framed and signed on the back

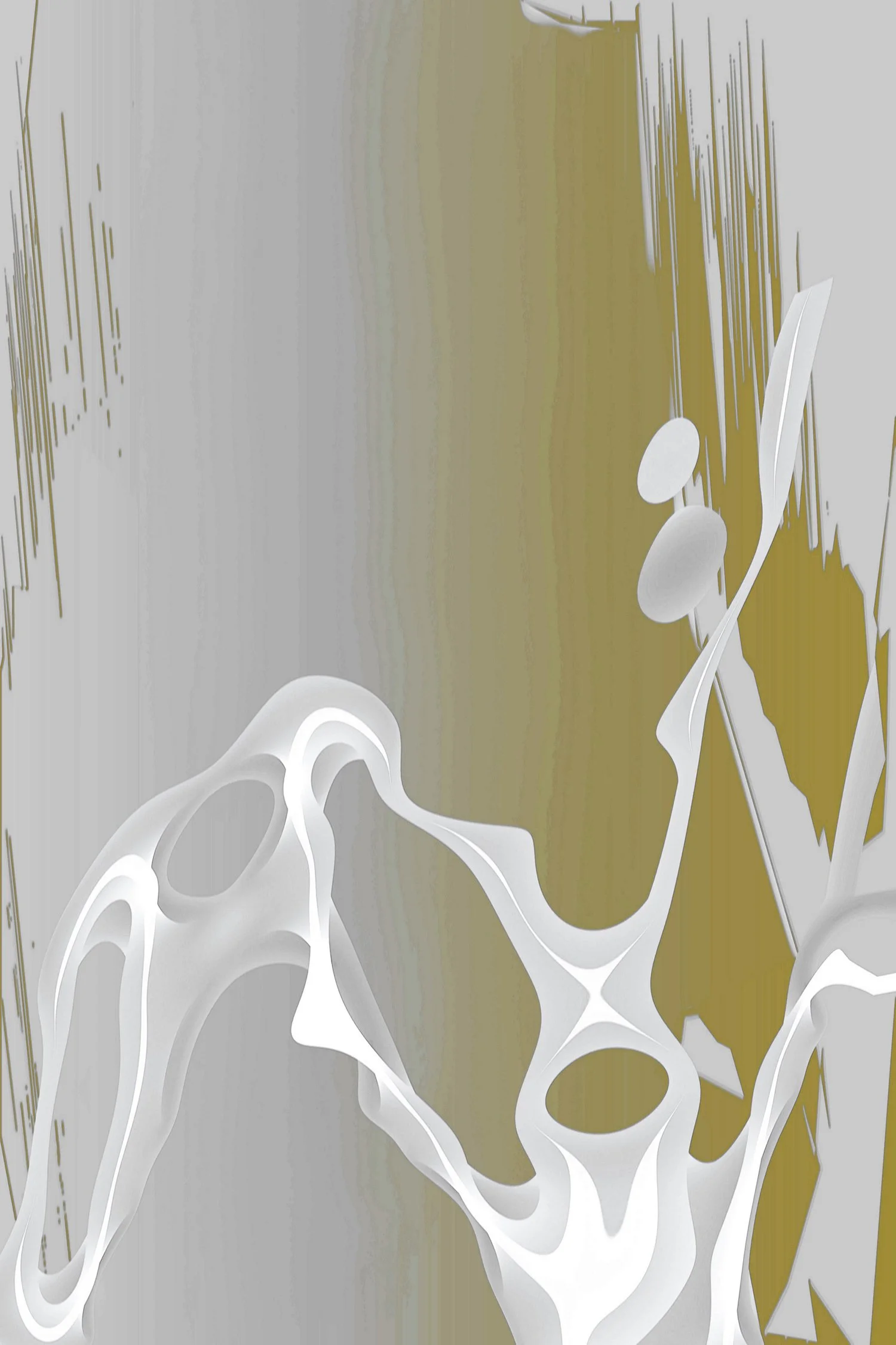

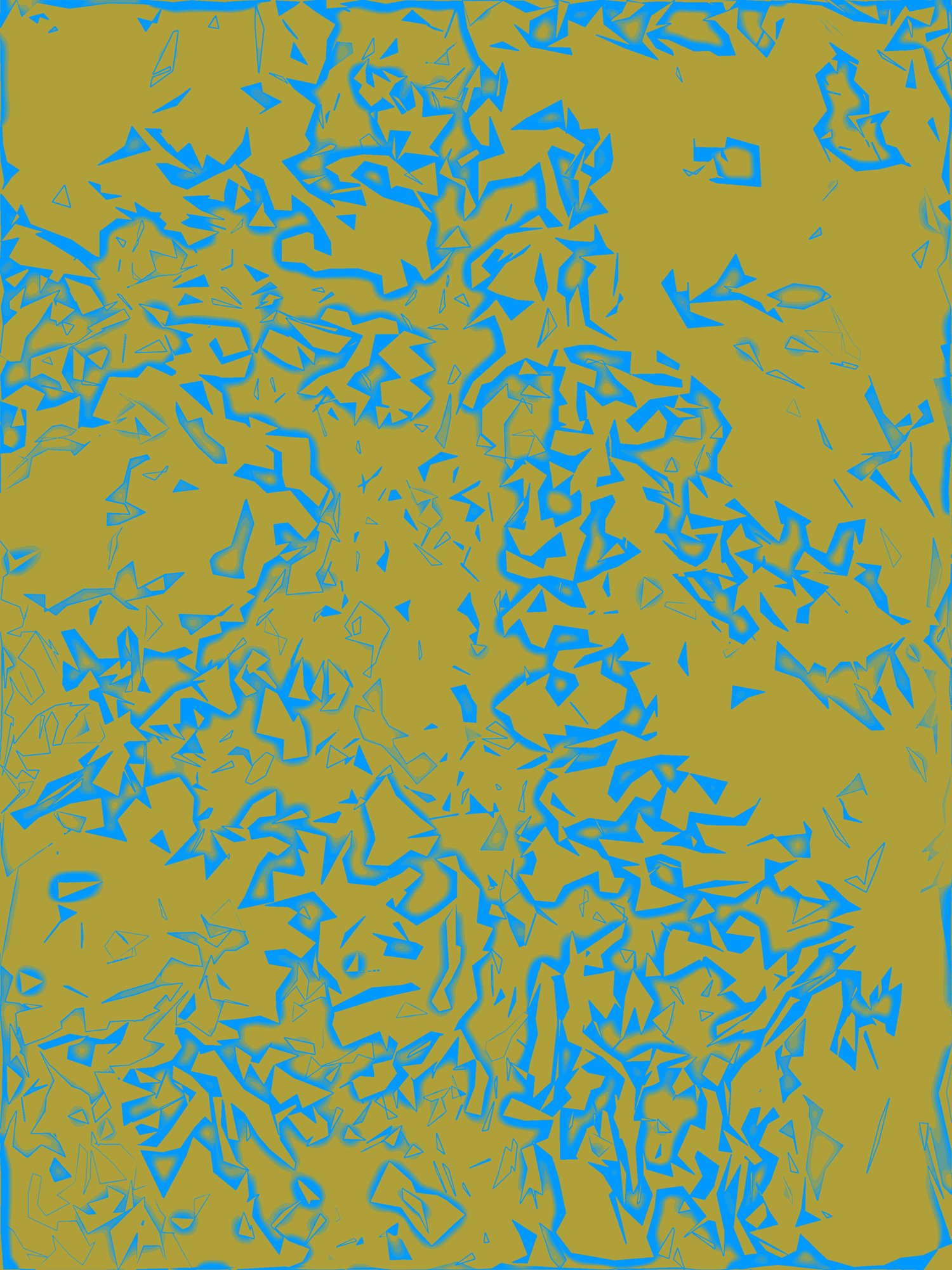

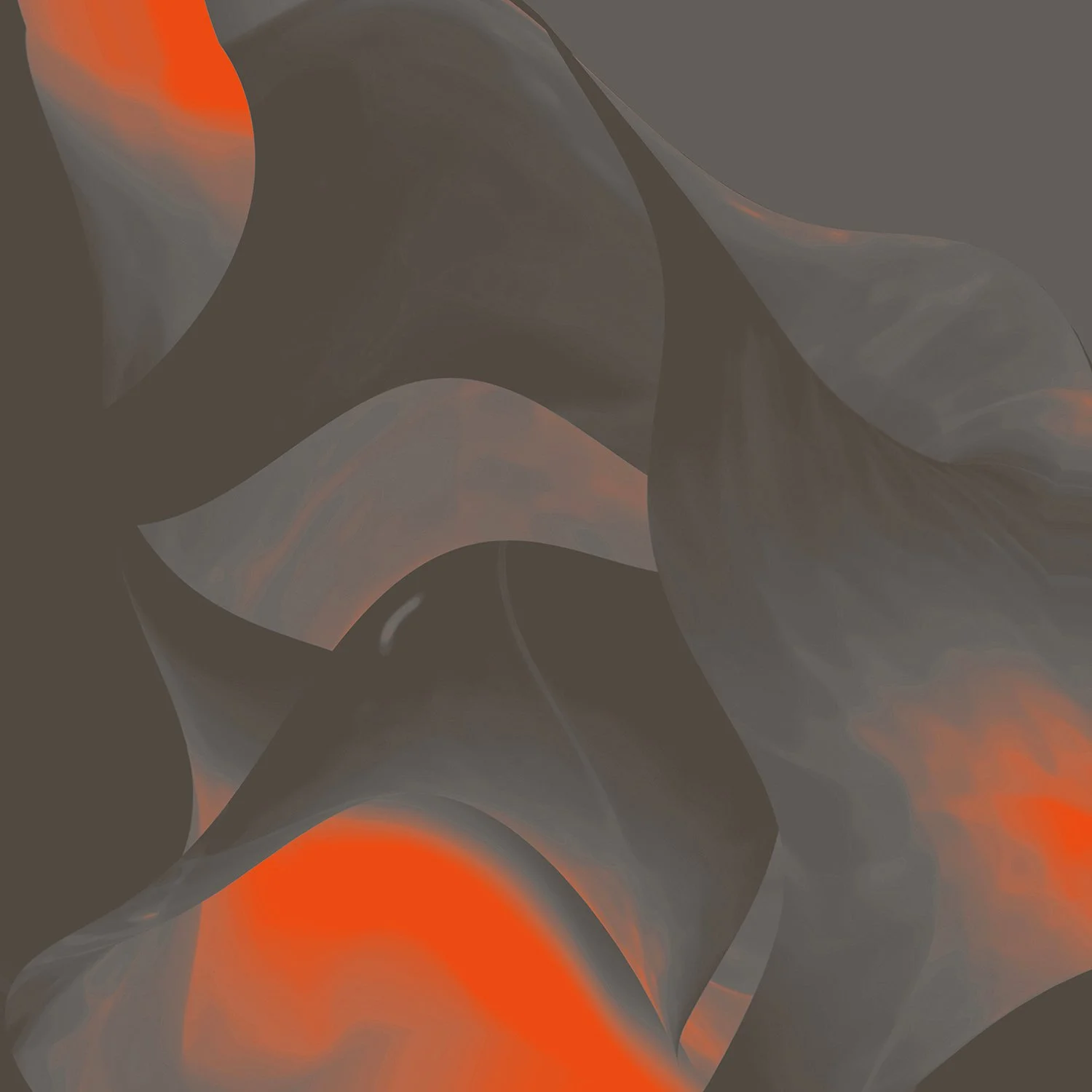

ursa_schoepper_grassland, 2026,experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 75 x 50 cm,framed and signed on the back

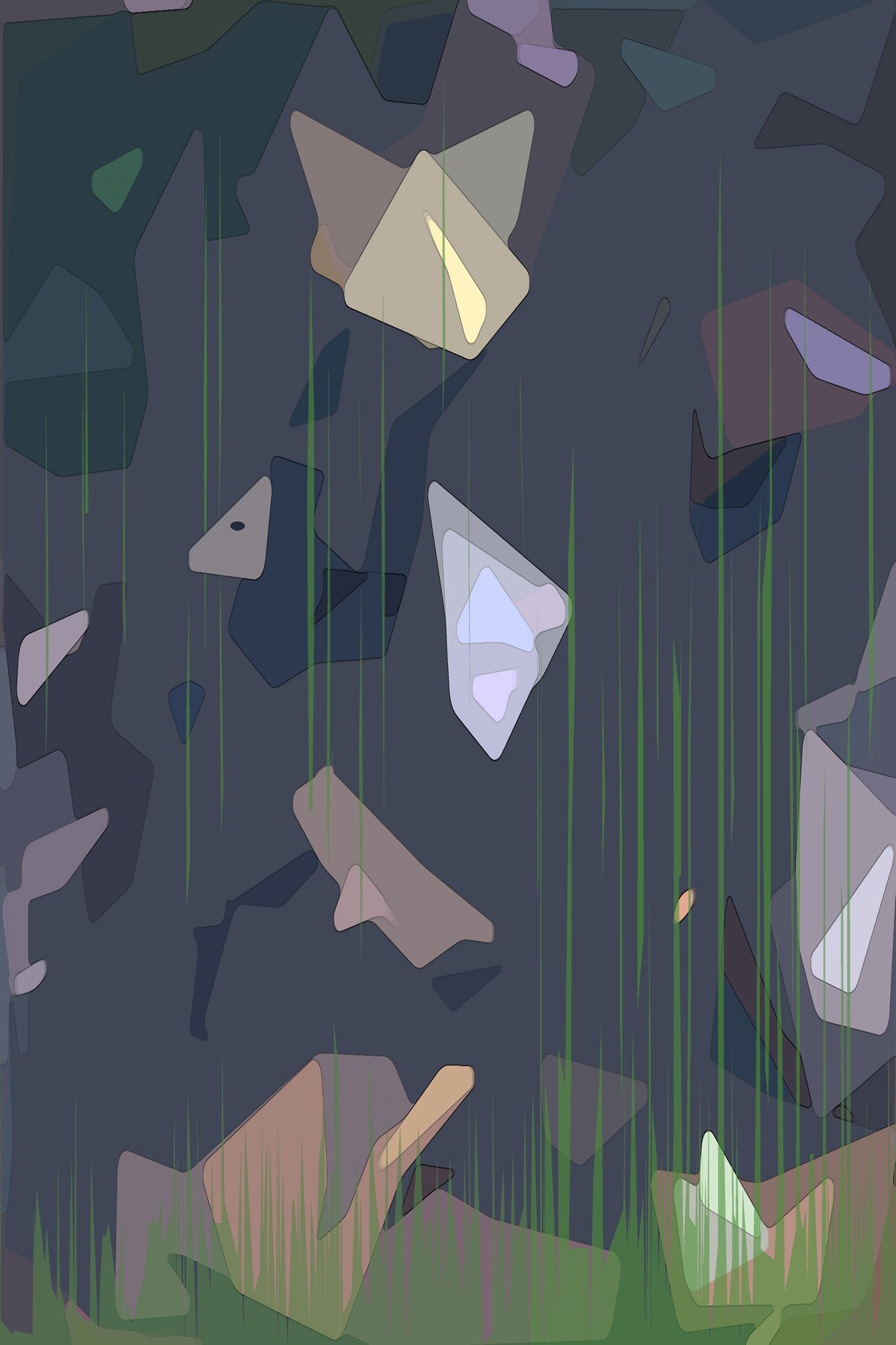

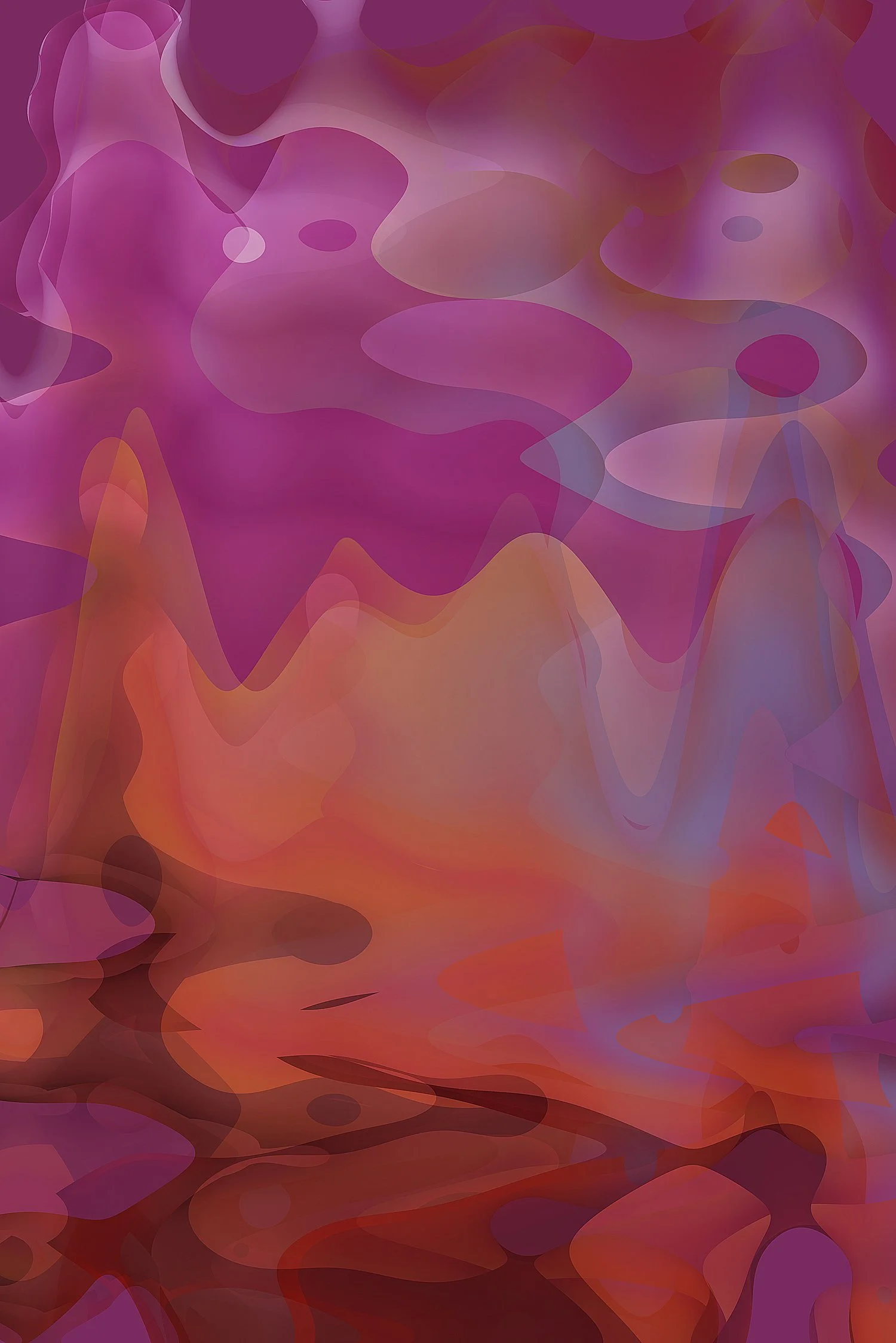

ursa_schoepper_sunken_paradise, 2025, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 80 cm, framed and signed on the back

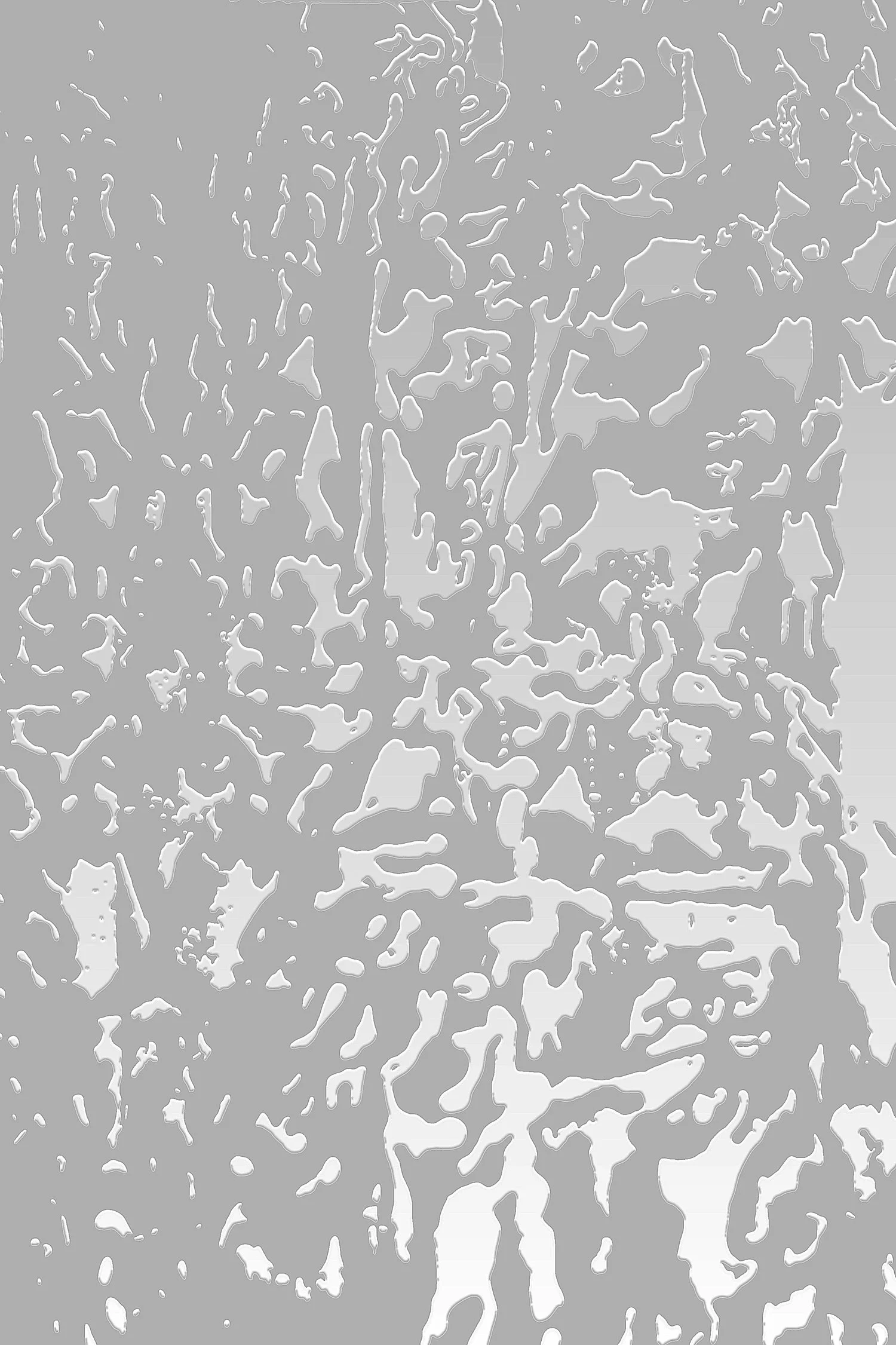

ursa_schoepper_antechamber_to_hell, 2026, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 80 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_memory_of_destruction, 2024, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 80 x 60 cm, framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_water landscape, 2024, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 90 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_ephemeral, 2026, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 80 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_ amoebendschungel, 2016, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 120 x 80 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_broken_ice, 2017, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on aludibond, 50 x 75 cm, framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_in_search_of_harmony, 2024 experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 80 x 80 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_unfold_in_space, 2024, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 80 x 80 cm,framed and signed on the back

ursa_schoepper_blow_up2, 2022, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 45 x 75 cm,framed and signed on the back

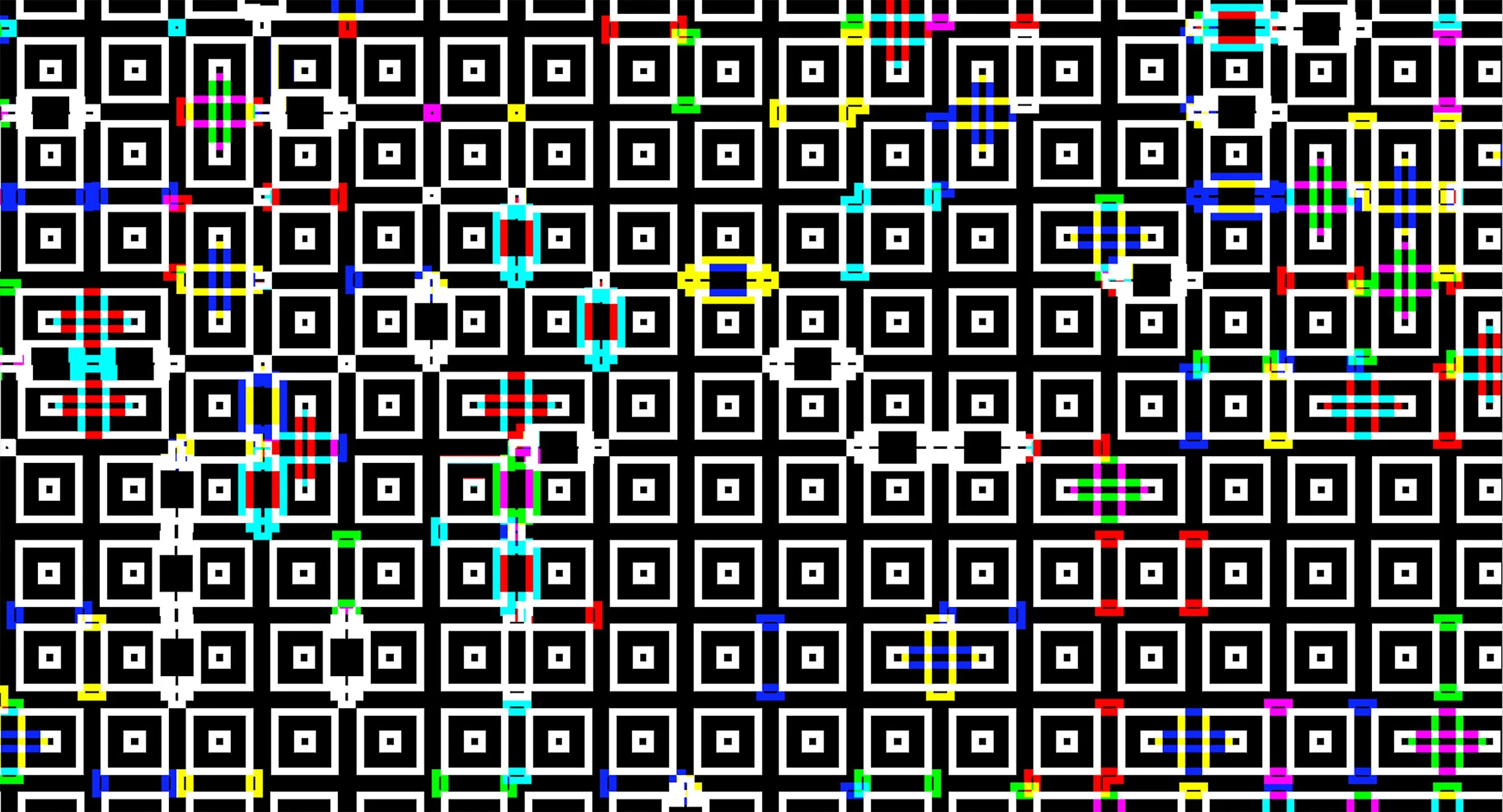

ursa_schoepper_inner_section, 2016, experimental digital fine art photography, colorpigment on AluDibond, matt, 30 x 40 cm, framed and signed on the back

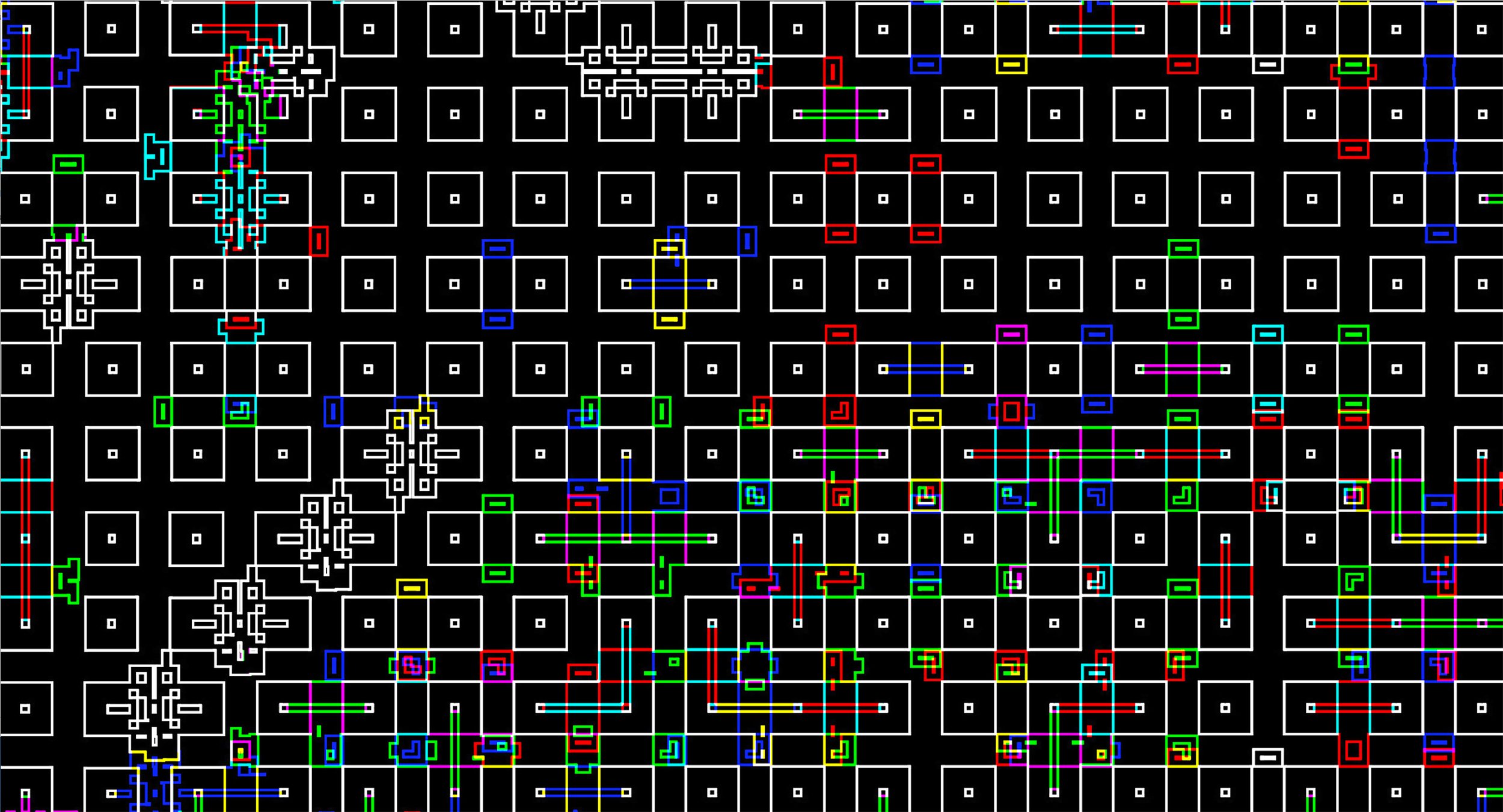

ursa_schoepper_internal structure_section, 2016, experimental digital fine art photography, color pigment on AluDibond, matt, 30 x 40 cm, framed and signed on the back